-

International Enforcement in a Global Economy

International economic activity involving multiple regulatory jurisdictions has increased significantly in recent decades. Between 1960 and 2009, imports of goods and services as a percentage of the global gross domestic product (GDP) have more than doubled.

Together, the United States and European Union economies account for more than half of the world’s GDP. In addition, cross-country corporate mergers as a percentage of total worldwide mergers have risen from 30% in 1998 to 45% in 2007.

This cross-border economic activity has spurred the creation of more fully developed antitrust policies and an increase in enforcement. Will domestic policy makers be tempted to use antitrust enforcement as a back door to protectionism? Are policies across jurisdictions naturally converging, or does enforcement differ for domestic and foreign firms?

Edward Snyder, dean of the Yale School of Management, and Analysis Group CEO Pierre Cremieux explored these issues in a recent study, "Global Antitrust Enforcement: An Empirical Assessment of the Influence of Protectionism."

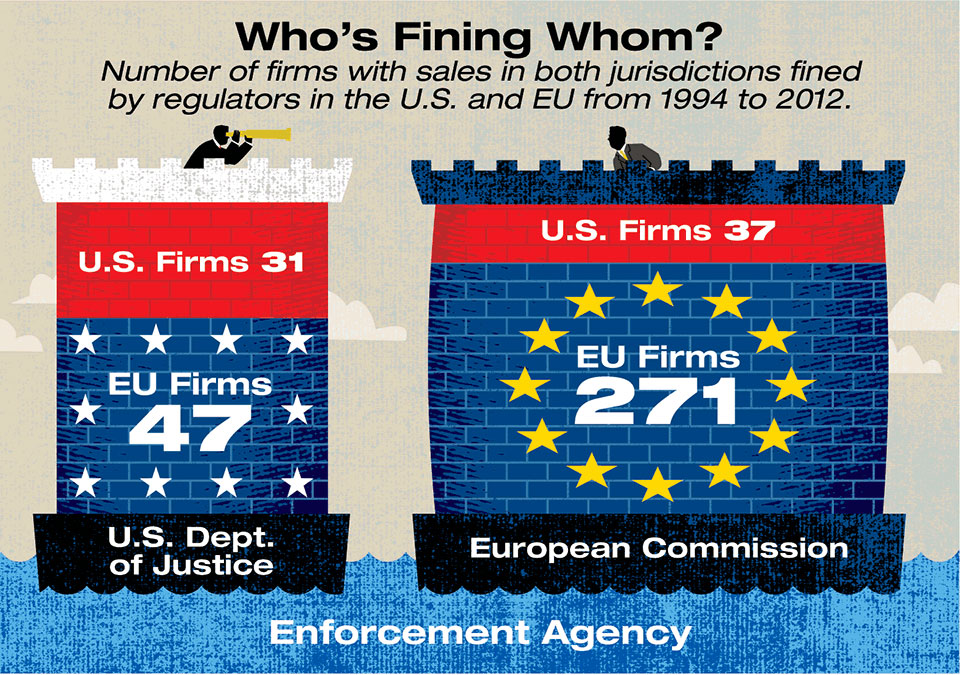

Professor Snyder and Dr. Cremieux posit that antitrust authorities may exhibit three possible approaches to enforcement (see right). They analyzed how EU and US antitrust authorities enforced anti-cartel laws from 1994 through 2012. They studied instances in which firms sold the same product lines in both jurisdictions, and examined the pattern of fines imposed to test whether the approach to enforcement was neutral, protectionist, or domestic. The authors found a surprisingly low level of overlap in enforcement across jurisdictions; most firms fined in one jurisdiction were not fined in the other.

They also found that authorities in both the European Union and United States are somewhat more likely to fine domestic rather than foreign firms. Furthermore, they discovered that EU authorities impose higher fines on EU firms, while US authorities impose higher fines on non-US firms.

The authors conclude that their results provide little support for the notion that antitrust enforcement of cartels has yielded to protectionism. The United States is less likely to fine foreign than domestic firms, but when it does, those fines are significantly larger. By contrast, the European Union is unambiguously domestically focused, with EU firms both more likely to be fined and to receive larger fines than their foreign counterparts.

-

“It is clear that domestic firms are more likely to be investigated by their own authority than by the foreign jurisdiction.”

— Edward Snyder, Dean, Yale School of Management

-

As a possible explanation for the European Union’s more aggressive domestic focus, Professor Snyder and Dr. Cremieux note that EU antitrust policies are relatively new compared with those in the United States. U.S. firms have been regulated by antitrust policy for more than a century – since the passage of the Sherman Act in 1890 – while the foundations of EU antitrust enforcement date back only to 1957, and the emergence of cartel enforcement to 1986. ■

Notes:

Fines by the U.S. Department of Justice are levied under Section 1 of the Sherman Act (Anti-Competitive Agreements). Fines by the EU European Commission are levied under Article 101 (formerly Article 81, Anti-Competitive Agreements).

Sources:

- U.S. DOJ, Antitrust Division, "Sherman Act Violations Yielding a Corporate Fine of $10 Million or More," as of May 22, 2009

- U.S. DOJ, "Annual Report FY 1999"

- U.S. DOJ Press Releases, Plea Agreements, Case Information, Indictment, and Briefs for Appellee

- EU European Commission Competition Policy, Antitrust Case Commission Decisions

- EU Annual Reports, 1994-2007

- EU Press releases

- EU Website, "European Countries"

View this page on a desktop or tablet to view an interactive graphic.

Three Possible Approaches to Enforcement

- Neutral enforcement refers to a regulatory environment in which factors such as a large number of bilateral trade agreements encourage authorities to cooperate and monitor the impact of anticompetitive conduct on other countries. The threat of retaliation can provide an incentive for authorities to favor a neutral approach.

- Protectionism can emerge when bilateral agreements lack teeth. When sovereignty or national interests trump nonbinding agreements, it falls on domestic antitrust authorities to restrain foreign competition by using fines or tariffs.

- Domestic orientation occurs when authorities focus on national firms, primarily because foreign firms are logistically more challenging to deal with and more complicated to investigate and prosecute. Also, authorities charged with protecting domestic consumers may believe that the deterrent effects of prosecuting domestic companies are greater, given their higher collective share of GDP.