-

Learning from Lehman: Lessons for Today

“The enemy is forgetting … as time passes and the memory of this [crisis] gets further in the rear-view mirror.”

– Former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke in a March 2018 interview on the 2008 global financial crisis

Recent dislocation in financial markets induced by the coronavirus pandemic brings back memories of the 2008 financial crisis. Although the root cause this time is a global health crisis, the impact on markets seen during the week of March 16, 2020, was eerily similar to that during the week of September 15, 2008, following the Lehman Brothers failure: Stock markets initially declined precipitously, volatility spiked, and investors fled en masse to safety.

Selling pressures in both instances were particularly acute in short-term credit markets, including money market mutual funds. These are the “cash-like” instruments that individuals and businesses often use as pseudo bank accounts.

In normal times, these instruments serve as stable and reliable sources of cash, but they are not free from risk during market sell-offs. As investor demand for cash increases, shares are redeemed, with the result that funds are forced to sell holdings precisely at the time that the market has no appetite to buy them.

In 2008, the Federal Reserve created new lending facilities that were intended to cushion markets from the panicked selling at the time. Now, during the pandemic-induced sell-off, the Federal Reserve has dusted off these same lending facilities to tackle similar market stress.

So far, these facilities have once again quickly provided desperately needed liquidity and helped calm short-term funding markets. In this article, we revisit research we conducted in the years following Lehman’s failure to reflect on these facilities’ history, mechanics, and impact on turbulent markets, then and now.

Then…

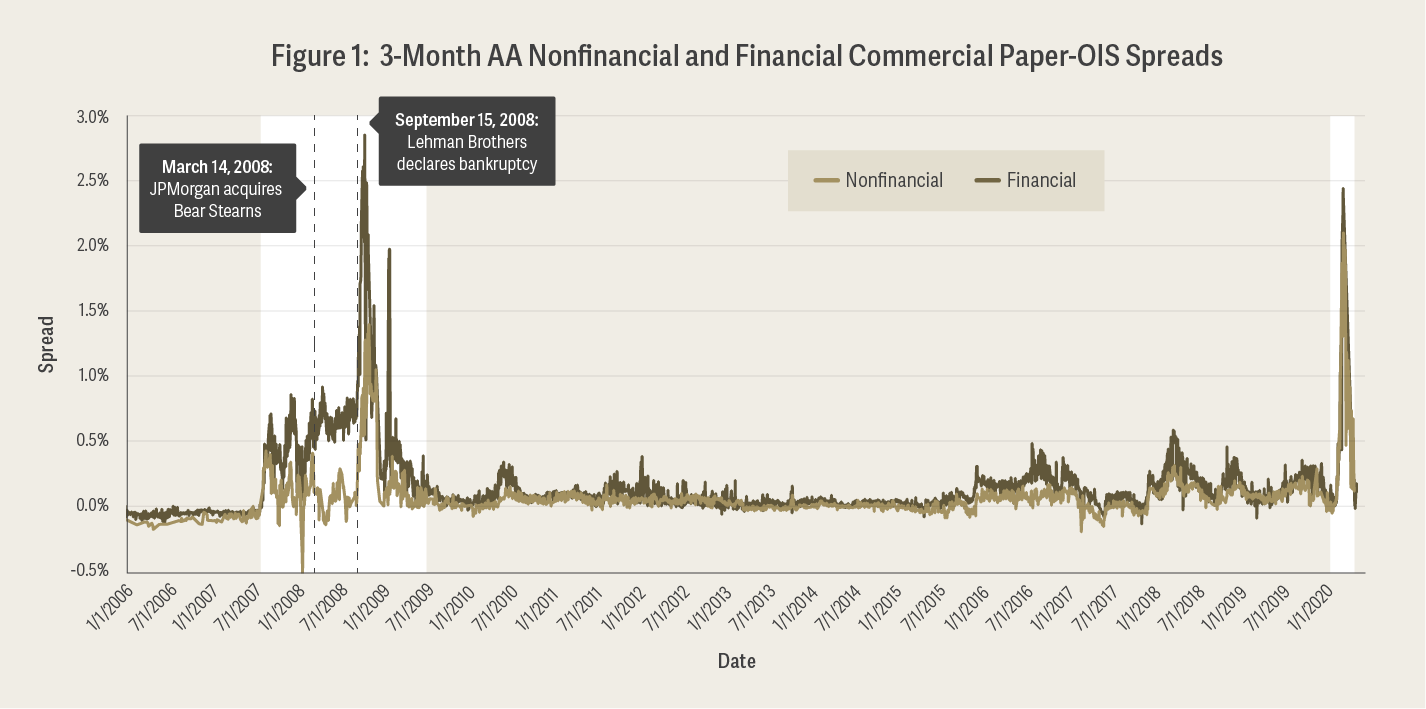

To evaluate the stress on short-term credit markets, we look to the difference between commercial paper (CP) rates and the overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate as a barometer of liquidity and short-term funding risk. CP is issued by financial and nonfinancial firms to fund short-term capital needs. OIS is a relatively risk-free measure associated with the federal funds rate.

An increase in the CP-OIS spread means that short-term unsecured borrowing rates are increasing relative to the federal funds rate. As such, an increase in this spread is consistent with increasing funding risk and decreasing liquidity for riskier assets.

Figure 1, which includes the CP-OIS spread for both financial and nonfinancial CP, shows that the spread increased in the summer of 2007, during the nascent months of the financial crisis as concerns began to emerge in the subprime mortgage market. The spread remained relatively high through the remainder of 2007, before increasing again during the March 2008 Bear Stearns crisis.

The chart shows that, during the 2008 financial crisis, the short-term funding stresses were more pronounced for financial firms than for nonfinancial firms. In contrast, in the recent market, both financial and nonfinancial CP-OIS spreads spiked to similar levels.

In the late 2000s, Bear Stearns, along with many other financial intermediaries, relied on the short-term “repo” markets for funding its balance sheet, making it vulnerable to a rapid decline in short-term liquidity. In a repurchase (repo) agreement, one entity (the borrower) sells a security to another (the lender), with an agreement to repurchase the security, or another security with similar features, at an agreed-upon date and price, plus interest. The borrower typically agrees to repurchase the security the next day.

However, lenders in these markets can cease providing necessary funding on short notice, and in March 2008, they did. Bear Stearns was unable to stop this modern-day bank run by itself, and on March 14, it received approval from the Federal Reserve to be acquired by JPMorgan.

The Fed rides to the rescue once…

Two days later, the Federal Reserve announced the establishment of the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), an emergency lending window through which the Federal Reserve extended secured overnight credit to primary dealers. To state it simply, broker-dealers could lend securities to the Federal Reserve in exchange for cash that they could then use to fund their businesses. This was intended to mitigate the chance of another Bear Stearns event where a broker-dealer was unable to find counterparties willing to lend to it via the repo market.

The rescue of Bear Stearns and the establishment of the PDCF did, in the immediate aftermath, calm financial markets, but the relief, as we now know, was not permanent. Short-term lending markets tightened again in the summer of 2008, before skyrocketing in the aftermath of Lehman’s bankruptcy filing on September 15 and the failure or near-failure of other large institutions (e.g., Washington Mutual and AIG) in the following weeks.

…and again

The PDCF, which was originally intended to support the borrowings of broker-dealers, did not have a broad enough reach to address the liquidity strain that occurred following Lehman’s failure, as the problem expanded from broker-dealers into the broader markets. The Federal Reserve expanded its intervention to support other critical short-term borrowing markets, such as CP, which is widely held by money market mutual funds.

Following Lehman’s failure and the market’s subsequent “flight to safety,” investors liquidated their CP holdings and redeemed shares in money market funds for fear that they would be stuck holding unsecured paper if the issuer failed or would face losses in money market funds that had previously been viewed as “cash alternatives.”

As a result, the CP daily rates spiked, and the Reserve Primary Fund infamously “broke the buck” on September 16, 2008. The CP-OIS spreads jumped to very high levels in the week following Lehman’s failure. (See Figure 1.)

To help ease the strains on CP and money market funds, the Federal Reserve expanded the credit facilities at its disposal. It announced the creation of the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) on September 19, 2008, and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) on October 7, 2008. These facilities were effective on September 22, 2008, and October 28, 2008, respectively.

AMLF: The AMLF was an immediate reaction to the Reserve Primary Fund breaking the buck and the further intensification of the sell-off in money market funds during the week of Lehman’s failure. Under this facility, money market funds that were being forced to sell holdings to meet redemptions, rather than selling into an illiquid market, could instead effectively sell their assets to the Federal Reserve. (Collateral eligible for pledge under the AMLF was limited to high-quality asset-backed CP.)

CPFF: Similarly, the CPFF served as a liquidity backstop to CP issuers. A special purpose vehicle (SPV), backed by the Federal Reserve and support from the US Treasury, purchased CP from eligible issuers.

Halting the run on the bank

Just as FDIC insurance was originally implemented during the Great Depression to prevent bank depositors from running to the bank when they grew concerned, these Federal Reserve facilities, in guaranteeing liquidity, were intended to provide comfort to market participants that their cash would be there when needed. By, in effect, putting the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve behind these short-term markets that are so critical to funding needs in today’s modern economy, the Federal Reserve substantially reduced the risk in these markets. With the establishment of these facilities, the Federal Reserve assumed much of the risk that investors in CP and money market funds had previously borne.

The strategy, along with other fiscal and monetary policy, worked. Although it took years for the global economy to recover from the events of 2008, short-term credit rates dropped quickly in the aftermath of this intervention, and largely returned to “normal” for more than a decade.

And now…

As the coronavirus pandemic intensified in late February and March of 2020, history began to repeat itself. As Figure 1 shows, given the nature of the pandemic, the impact on nonfinancial CP was even greater in March 2020 than in 2008, presumably because the widespread economic shutdown in response to the health crisis immediately affected nonfinancial companies, whereas the previous financial crisis most directly affected financial firms.

The return of the PDCF…

On March 17, 2020, almost 12 years to the day after creating the PDCF, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) announced its re-establishment. (In the interim, the facility had been closed since February 2010.) According to the Federal Reserve’s press releases, the stated purpose of today’s PDCF is “to support the credit needs of American households and businesses,” while the 2008 facility was created to “bolster market liquidity and promote orderly market functioning.”

Despite the difference in objective, the spirit and mechanism are the same: Through the facility, the FRBNY provides liquidity to short-term credit markets by extending overnight credit to primary dealers secured by eligible collateral.

…of the CPFF…

Also on March 17, 2020, the Federal Reserve announced the re-establishment of the CPFF to “support the flow of credit to households and businesses.” The facility again involves an SPV, supported by the Federal Reserve and US Treasury, purchasing CP directly from eligible companies.

…and of the AMLF (now the MMLF)

Finally, on March 18, 2020, the Federal Reserve announced the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF), which functions as the AMLF did during the 2008 financial crisis. The MMLF allows eligible financial institutions to borrow from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, provided that the institutions pledge assets they purchased from money market mutual funds. In this way, the facility again promotes liquidity to the money market mutual funds.

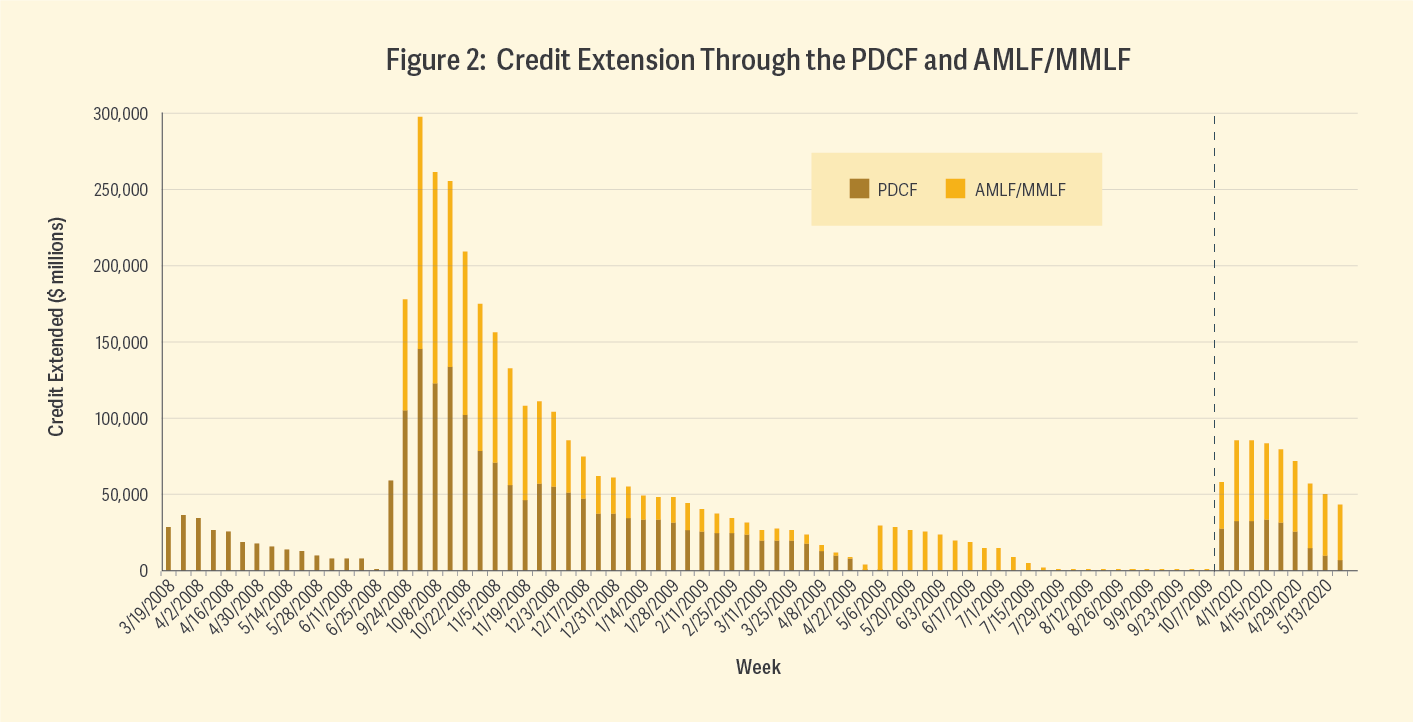

The facilities have been actively used by borrowers. Figure 2 shows that, by March 25, 2020, nearly $30 billion in financing had been extended to primary dealers by the FRBNY through the PDCF, an amount on par with the credit extended through this facility during much of the 2008 financial crisis. Figure 2 also shows that the activity in the MMLF, while below the peak usage of the AMLF during the 2008 financial crisis, has been large, peaking at over $50 billion.

As in the aftermath of Lehman’s failure, these facilities appear to have helped calm the short-term credit markets, with short-term credit spreads narrowing to pre-pandemic levels within a week of the facilities’ establishment. The Federal Reserve acknowledged in its May 2020 Financial Stability Report that markets improved after the announcement of these facilities and that market participants have largely stopped new borrowing through the facilities.

-

The second time around

During the pandemic crisis, the Federal Reserve has reacted faster in implementing many of the tools at its disposal, and the markets have responded more quickly. This time around, with the legal and logistical blueprints already in hand, the FRBNY was able to open the PDCF within a matter of weeks, rather than months. The Federal Reserve was able to quickly use these facilities to inject liquidity into the stressed markets, and generally signal its support of the markets.

With a decade of experience under their belts, market participants also already understand how to use the facilities, and likely were confident, given the experience in 2008, that the Federal Reserve could successfully intervene to inject substantial liquidity into the markets. These factors likely have contributed to the indications so far of a faster market response. For example, the spread between CP and OIS rates dropped faster than before once the new lending facilities became available.

Low borrowing levels suggest that the direct implementation cost of these facilities is low. As the markets have calmed, new borrowing from the facilities has decreased, and so the Federal Reserve has not yet been left holding a large amount of risky debt from these facilities. While more research is needed, this suggests that the benefit of calming short-term borrowing markets during these crises has not resulted in a large direct cost to the Federal Reserve. In fact, the Federal Reserve was not holding any securities in these facilities when they were closed after the 2008 financial crisis.

The rollout has been slower for new facilities created specifically to target needs unique to the pandemic. As a result of stay-at-home orders and advisories being implemented across the nation, nonessential businesses have been shut down, millions of employees have been laid off or furloughed, and municipalities are facing severe budget shortfalls. In response, the Federal Reserve and the US federal government are implementing several first-time programs and new legislation.

These include larger relief packages and additional credit facilities such as: the CARES Act (March 27), the Paycheck Protection Program Lending Facility (April 6), the Main Street Lending Program (April 9), and the Municipal Liquidity Facility (April 9). Being new, however, these actions face heavier scrutiny from Congress as to how they will be implemented, which entities and individuals will be eligible, and how they will be distributed and monitored going forward.

While it remains to be seen how successful such first-time programs will be at blunting the economic downturn, the immediate impact of resurrecting the 2008 financial crisis-era facilities has thus far been promising. ■

-

Laura Comstock, Principal

Michael Holland, Managing Principal

Peter Tufano, Peter Moores Dean and Professor of Finance, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

From Forum: 2020.