-

Platforms, Competition, and the Crisis: Arun Sundararajan on How Restaurants Have Adapted During the Pandemic

The spread of the coronavirus and ensuing stay-at-home orders have caused tremendous adversity in the restaurant business. For April 2020, the first full month of the pandemic-induced shutdown, the US Census Bureau reported a nearly 50% drop in business for food services and drinking places, reflecting losses of more than $30 billion in that month alone. Independent restaurants – which often lack the access to credit and financing options enjoyed by their larger chain counterparts – have absorbed an especially large share of the blow. Faced with these difficult prospects, and with dine-in prospects still severely curtailed, many restaurants have looked to food delivery apps such as Uber Eats and DoorDash to stabilize and sustain their business.

The effects of this migration and the role that digital platforms play in facilitating economic resilience are the topics of a recent research paper coauthored by Analysis Group academic affiliate Arun Sundararajan, of the NYU Stern School of Business. Together with two colleagues – Manav Raj of NYU Stern and Calum You of Uber – Professor Sundararajan studied order-level data from the Uber Eats platform for consumers ordering food in five American cities to determine the effect that the platform had on restaurant activity.

In this Q&A, Managing Principal Rebecca Kirk Fair spoke with Professor Sundararajan about how this new paradigm has altered restaurants’ business models, the competitive effects that digital platforms create, and whether the digital shift catalyzed by the lockdown will outlive the pandemic.

What led you to undertake this study?

Arun Sundararajan: Harold Price Professor of Entrepreneurship; Professor of Technology, Operations and Statistics, NYU Stern School of Business

The economic lockdown has been a very difficult time for smaller restaurants, with many closing temporarily or permanently. Our study was motivated by interest in whether new channels created by food delivery platforms like Uber Eats and DoorDash have a tangible effect on the survival of independent restaurants during such a crisis. In effect: Were the platforms making it possible for these restaurants to at least partially offset the declines in business they were suffering by having to close their doors to diners?

So, in one sense, our paper was about a particular economic effect of the pandemic on one sector, but in another, it adds to a long line of research into how the digital economy continues to disrupt and/or expand traditional modes of business.

However, much of this research has focused on the firms creating and organizing the platforms. Much less attention has been paid to the supply side of the platform – that is, the providers themselves – despite the fact that such providers are critical to value creation and make up the vast majority of businesses in a platform ecosystem. Our work aims to help fill that gap.

How did you conduct your analysis?

We used order-level data from Uber Eats between February 1 and May 1 for smaller restaurants across five major US cities (Atlanta, Dallas, Miami, New York, and San Francisco). We measured demand for and performance of each restaurant through the count of orders a restaurant received each day.

In studies like this, it’s often useful to have a control group against which to measure the cities that are subject to the exogenous shock. The near-universal effect of COVID-19 across the country made that impossible, but we may update the analyses as heterogeneous time-varying impacts of COVID-19 in various cities emerge in the future.

Some results seem intuitively likely – for example, that Uber Eats would have experienced a sharp rise in independent restaurants joining the platform as foot traffic dried up.

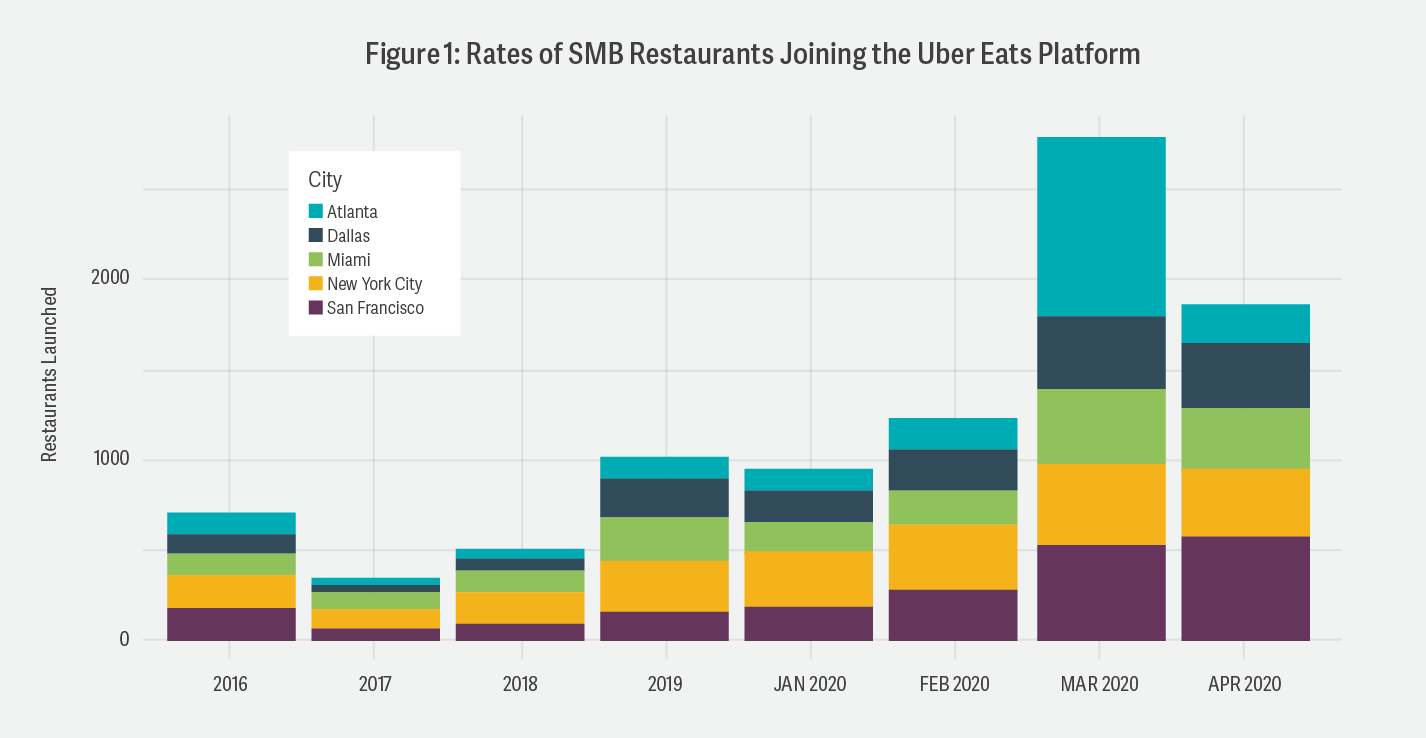

This effect is indeed clear from the data. Across the cities we studied, sign-ups by independent restaurants to the Uber Eats platform increased by 128% in March relative to February 2020, and then by 51% in April – both quite dramatic jumps. (See Figure 1.) Further, all five cities witnessed significant jumps in total order volume on the platform across restaurants – in San Francisco, for example, by as much as 51%.

What’s more interesting is that we saw total daily orders on the platform increase despite the fact that many restaurants either shut down completely or cut back on the hours in which they were available to take orders. In some cities the drop in these “supply hours” was quite large – almost 50% in New York. Considering the extent of this structural supply shock, the fact that the total number of orders actually increased tells us that restaurants have dramatically raised their order velocity over these apps, which is the number of orders fulfilled per supply hour. In both New York and Dallas, the order velocity over the Uber Eats platform more than doubled.

Note: SMB = small to medium-sized businesses

What explains the sharp rise you found in order volume?

There are a number of possible reasons. Clearly, one driver was a lack of dine-in options, and a consequent substitution effect. Another could have been the challenge in obtaining groceries in April, because of supply problems and health-related fears, which would have led to an expansion in platform-based restaurant orders.

Did you expect this rise in order volume?

It was unclear at the outset what the data would tell us, since such factors as consumer perceptions and supply constraints could have reduced overall demand for food delivery services. For example, fears about letting packages handled by others into one’s own house may well have worked against an increase in order volume. So would the absence of one’s favorite restaurant on the Uber Eats platform. In the end, though, these mitigating factors were greatly outweighed by those that induced a rise in order volume.

The large influx of new independent restaurants on the platform must have had some effect on competition among restaurants there.

To get at that question, we’ve created a number of ways to quantify competition, including a new network-based measure. The approach described in the paper first categorized restaurants by their primary cuisine designation, and then, within each category, measured the effect of the increased supply of restaurants on the overall volume of orders.

Our results highlight the dual economic effects of an increase in the number of competitors. On the one hand, having more restaurants on the platform leads to an increase in total consumer activity. On the other hand, a larger number of options on the platform increases the competitive intensity and decreases, on average, the number of orders each individual restaurant receives. What’s good for the platform, in other words, does not always correlate with outcomes for each individual restaurant.

Whether the expansionary network effects of having access to a greater user base will, over time, smooth out the competitive effects of more dining options on the platform is something that will only become clear over time. We’re also in the process of refining these findings with a new way of measuring competition, which, for each pair of restaurants, measures how intensely they compete with each other based on how much their consumer bases overlap, thus creating, in a sense, a network of competitive intensity across all restaurants.

That assumes that many of the restaurants that have migrated to Uber Eats will remain there more or less permanently. Which raises a broader question: Do you think that restaurants that joined food delivery platforms will remain there, even when the pandemic has subsided and they’re able to offer normal dine-in options again?

I think we’re at an inflection point for the “scale without mass” business model, and that the fraction of spending on eating out will shift very significantly towards platforms in the next five years. On the supply side, the costs of dine-in will go up because of social distancing and cleaning protocols, making online orders increasingly attractive to independent restaurants. Platforms and digital distribution channels lower the costs of entry for small providers, enabling them to reach buyers more easily and providing them with flexibility. Many of these restaurants may not even open a storefront, opting instead to be cloud kitchens that are online only. On the demand side, more consumers have experimented with the delivery model, and history teaches us that this kind of digital shift can be persistent, outliving its initial catalyst.

Regardless, an incontrovertible conclusion that can be drawn from our study is that platforms like Uber Eats have significantly contributed to the survival of small businesses, many of which would not have been able to endure the economic shocks associated with the pandemic without this kind of digital channel. That will almost certainly reinforce the message that these platforms are here to stay, and that the restaurants that survive in the future will be those that embrace the innovation and opportunity created by platforms. ■

From Forum 2020.