-

Deceptively Simple: Survey Evidence in Food and Beverage False Labeling Class Actions

With false labeling class actions on the rise, rigorously designed surveys can provide contextual clues needed to explain how the “reasonable consumer” makes purchasing decisions.

In recent years, filings for food and beverage class actions have grown, especially those involving allegations of false or misleading product labeling. These kinds of allegations often revolve around claims that consumers are being deceived by the language a company uses to characterize the contents or source of a product, such as saying it is “vanilla flavored,” claiming it is “all natural,” or implying that it is produced in a specific location. Other allegations may involve claims of deception by the omission of information about a product – such as the presence of potentially harmful ingredients – that plaintiffs allege may influence some consumers’ purchase decisions.

The “Reasonable Consumer” Rules the Day

The outcomes in many of these types of cases are grounded in the “reasonable consumer” standard. In a false labeling case involving snack foods, In re: Kind LLC “Healthy and All Natural” Litigation, the Honorable Naomi Reice Buchwald cited precedents defining this “objective standard”:

“[The reasonable consumer standard requires a probability] that a significant portion of the general consuming public or of targeted consumers, acting reasonably in the circumstances, could be misled.”– Lavie v. Procter & Gamble Co., 129 Cal. Rptr. 2d 486, 495 (Ct. App. 2003) [emphasis added]

Other recent decisions similarly have turned a spotlight on the need to consider “circumstances” – that is, what contextual, real-world information does a “reasonable consumer” have available when making a purchasing decision? For example, in a case study for the 2022 edition of Top Food and Drug Cases (an annual publication of the Food and Drug Law Institute, or FDLI), Analysis Group authors Rebecca Kirk Fair, Rene Befurt, and Genna Liu wrote:

What information may be relevant when evaluating whether a reasonable consumer would be misled by a product’s labeling? In Moore v. Trader Joe’s Co., the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reinforced the importance of contextual clues beyond the at-issue product label to determine whether a reasonable consumer would hold what the court described as an “unreasonable or fanciful” interpretation of Trader Joe’s manuka honey product label. … Specifically, the court of appeals highlighted the need to consider consumers’ background knowledge, the product’s price point, and the product type.

In many cases, the “reasonable consumer” is one who makes their purchase decision based on contextual information available in the real-world setting. Therefore, balancing the realities of the market in which a product was purchased with the thought process of consumers in that market is integral to understanding the perspective of the “reasonable consumer.”

It is especially important to “get it right” in food and beverage class actions, which typically involve huge numbers of consumers and high sales volumes, exposing defendants to a greater risk of high-dollar settlements. Indeed, ignoring the consumer’s experience in the real world can carry a high cost, as was made clear from the ruling in Kind. There, Judge Buchwald explained the type of evidence required by the court: “Plaintiffs have not introduced evidence that could allow a factfinder to determine a reasonable consumer’s understanding of ‘All Natural,’ and therefore, their claims cannot survive defendant’s motion for summary judgment.” [emphasis added]

What Makes a “Reasonable Consumer”?

Introducing evidence that allows factfinders to determine the actions of a “reasonable consumer” in any given circumstance is not a simple exercise. Fundamentally, the “reasonable consumer” standard depends on a solid understanding of purchasing behavior – that is, how do consumers make their decisions in the real world?

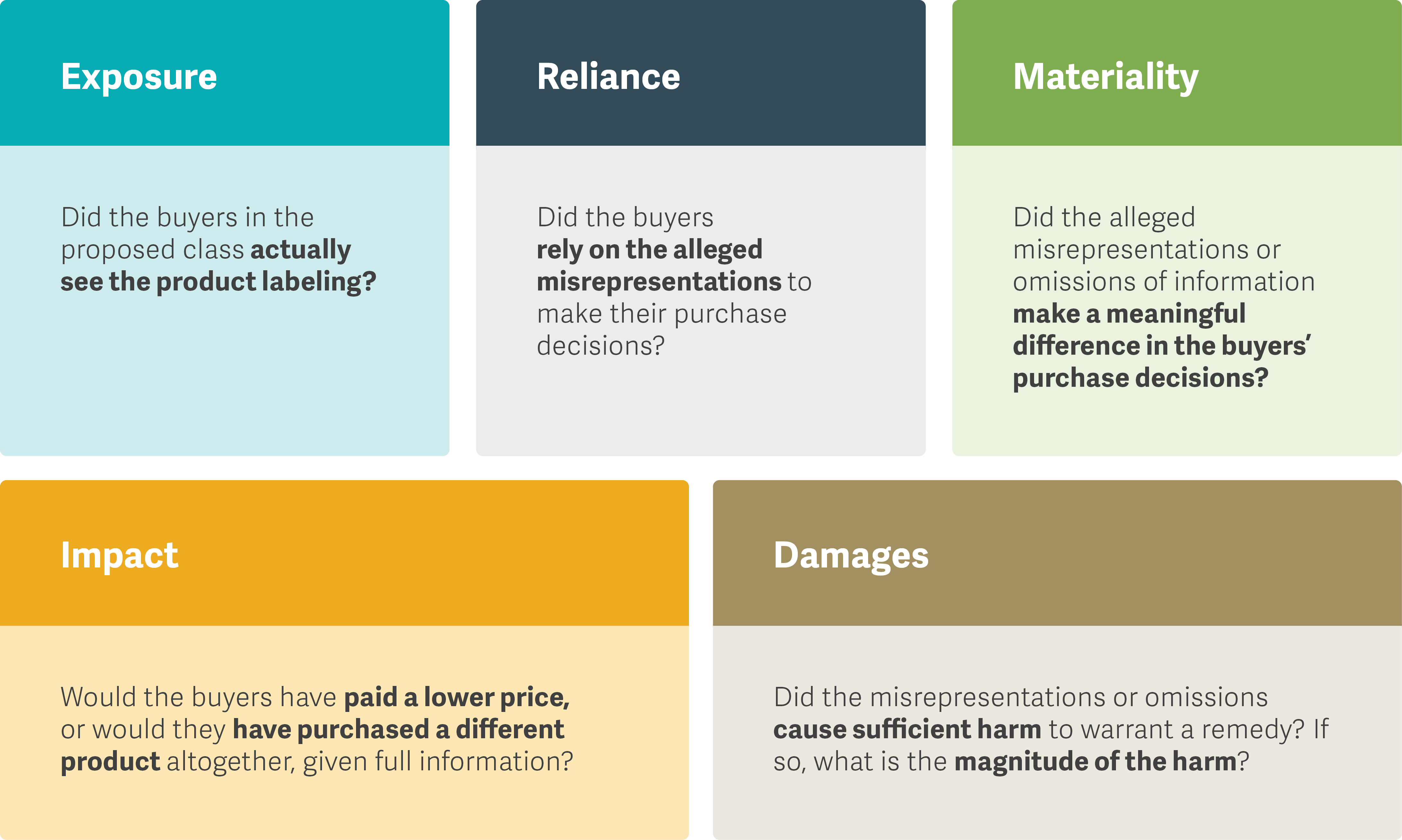

This means assessing, among other factors, class members’ exposure to the alleged misrepresentations, and then their reliance on that information during the purchasing experience. Finally, plaintiffs must be able to demonstrate whether or not the misinformation, or the omission of information, caused actual harm – for example, by inflating the purchase price, or by steering the consumer away from alternative purchases.

Evidence of such factors may come from consumer surveys in the right circumstances. For example, the ruling in a 2018 case involving vitamin supplements, Hughes v. Ester C Co., states, in part, “To satisfy the reasonable consumer standard, a plaintiff must adduce extrinsic evidence—ordinarily in the form of a survey—to show how reasonable consumers interpret the challenged claims.” [emphasis added]

A survey – as long as it is well constructed, properly administered, and fit to the specifics of the case – may help a litigant answer several key questions in false labeling cases, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: What Can Consumer Surveys Tell You?

Not All Surveys Are Created Equal

However, not any old survey will do. In dismissing the claims in Kind, Judge Buchwald tossed out the results from the plaintiffs’ consumer survey, stating that it was biased, had a limited scope of inquiry, and misleadingly led surveyed consumers to pick the plaintiffs’ preferred answers.

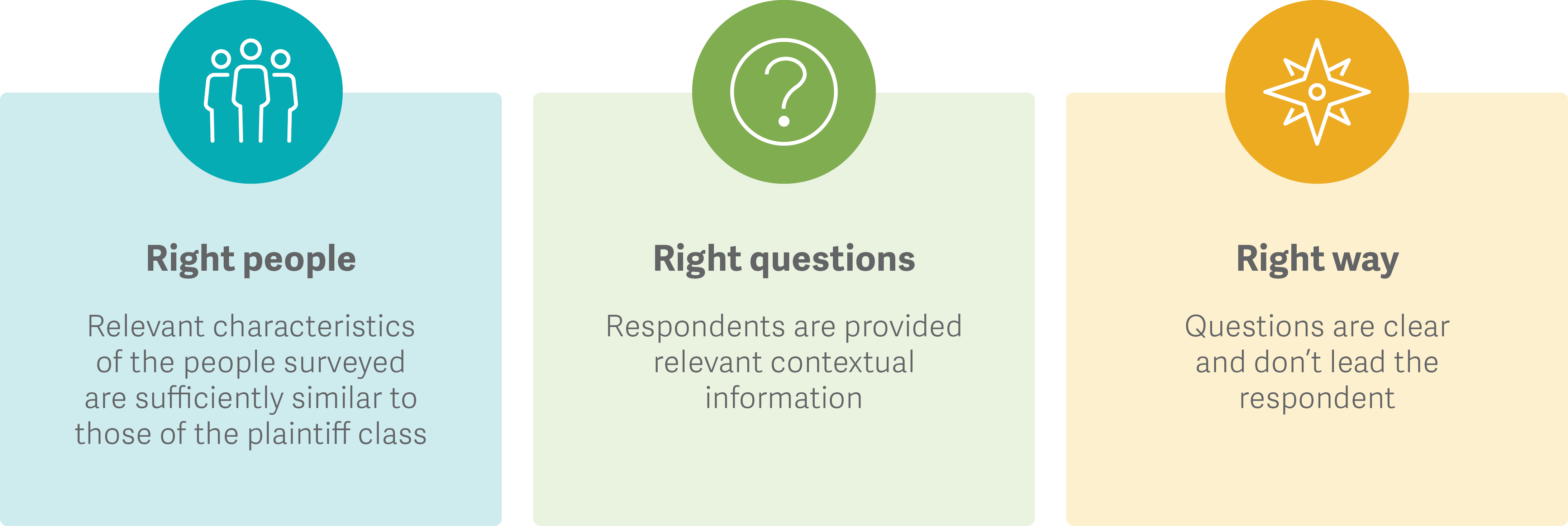

Well-designed surveys are made with the “right ingredients.” Surveys may seem deceptively simple, but to be admissible as evidence, they must be scrupulously conducted and administered to ensure that they ask the right questions of the right people in the right way. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: What Are the Ingredients of a Well-Designed Survey?

If a survey fails at any of these three prongs, the expert may risk having their survey analysis accorded minimal weight or even excluded altogether.What Might the Future Hold?

Rigorous survey evidence is likely to remain crucial in false labeling litigation as these cases continue to be filed in the food and beverage industry. Filings also are likely to grow among “functional*,” legalized CBD, eco-friendly**, and other newer types of products, but the need for evidence that helps factfinders discern the purchasing behavior of the “reasonable consumer” will remain the same. In addition, the same analytical framework applies to surveys used in other types of false advertising cases and involving different types of products (e.g., Molson Coors, LLC v. Anheuser-Busch Companies, LLC).

Consumer class actions, particularly where there are false labeling allegations, rely on formal definitions and advanced applications of marketing concepts. In their 2022 article “Academia in Court: How Marketing Scholarship Informs The Law,” Analysis Group’s affiliated experts David Reibstein and Suneal Bedi, along with Managing Principal T. Christopher Borek and Principal Robert L. Vigil, concluded: “Our judicial system relies on marketing concepts. The court system’s reliance on marketing research will likely only increase as academia improves best practices and uncovers new methods for analyzing consumer behavior.”

This is especially true in consumer class actions that depend on the “reasonable consumer” standard. To be admissible and persuasive in a court of law, marketing research must go beyond academic theories divorced from marketplace realities or overly simplistic reliance on “common sense.” Fortunately, a wealth of established and vetted tools exist that, when skillfully and appropriately deployed, may assist a court in determining whether any alleged misrepresentations or omissions of information ultimately made a difference when the “reasonable consumer” was making up their mind. ■

* Products purporting to have additional benefits beyond standard nutrition, such as hydration, mindfulness, and relaxation

** Particularly given growing attention to ESG (environmental, social, and governance) disclosures

Laura O’Laughlin, Principal

Brendan Rogers, Vice President

From Forum 2022.