-

New Bottles for Old Wine? A New Focus on Antitrust in Labor Markets

On the heels of the Biden administration’s executive order on competition, antitrust issues in labor markets are coming under increasing scrutiny from enforcement agencies. Do the agencies already have the tools to confront these issues?

Antitrust enforcers are putting a new focus on competition in labor markets, with criminal enforcement of wage-fixing and no-poach agreements, investigations of labor market effects in merger reviews, and inquiries into employment terms like non-compete agreements.

The roots of this increased scrutiny lie in the joint release by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) of the Antitrust Guidance for Human Resource Professionals in 2016. The Guidance affirmed the agencies’ view that the antitrust law applies with equal force to labor markets and that investigations of wage-fixing or no-poach agreements could result in criminal charges.

This push received an additional boost during the first year of the Biden administration, with its July 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, which highlighted the labor market as one of the key areas in which the administration intended to “enforce the antitrust laws to combat the excessive concentration of industry, the abuses of market power, and the harmful effects of monopoly and monopsony.”

In a December 2021 joint workshop titled “Making Competition Work: Promoting Competition in Labor Markets,” officials from both agencies emphasized labor market-focused priorities for antitrust enforcement. During that workshop, Jonathan Kanter, assistant attorney general for the DOJ’s Antitrust Division, described competition in labor markets as “a moral issue” and underscored the DOJ’s plans to criminally prosecute “agreements among employers to fix wages” and “agreements to allocate markets for workers.”

“[Wage-fixing agreements] fit squarely within the ambit of the antitrust laws. … Put simply, employees, like consumers, are entitled to the benefits the Sherman Act affords and protects.”– Jonathan Kanter, Assistant Attorney General, DOJ Antitrust Division

Similarly, FTC Chair Lina Khan highlighted the Commission’s labor market goals, including scrutinizing non-compete clauses and non-disclosure agreements through both enforcement and rulemaking.

“We are redoubling our commitment to investigating potentially unlawful transactions [and] anticompetitive conduct that harm workers. In particular, we must scrutinize mergers that may substantially lessen competition in labor markets, recognizing that the Clayton Act’s purview applies to product and labor markets alike.”– Lina Khan, Chair, FTC

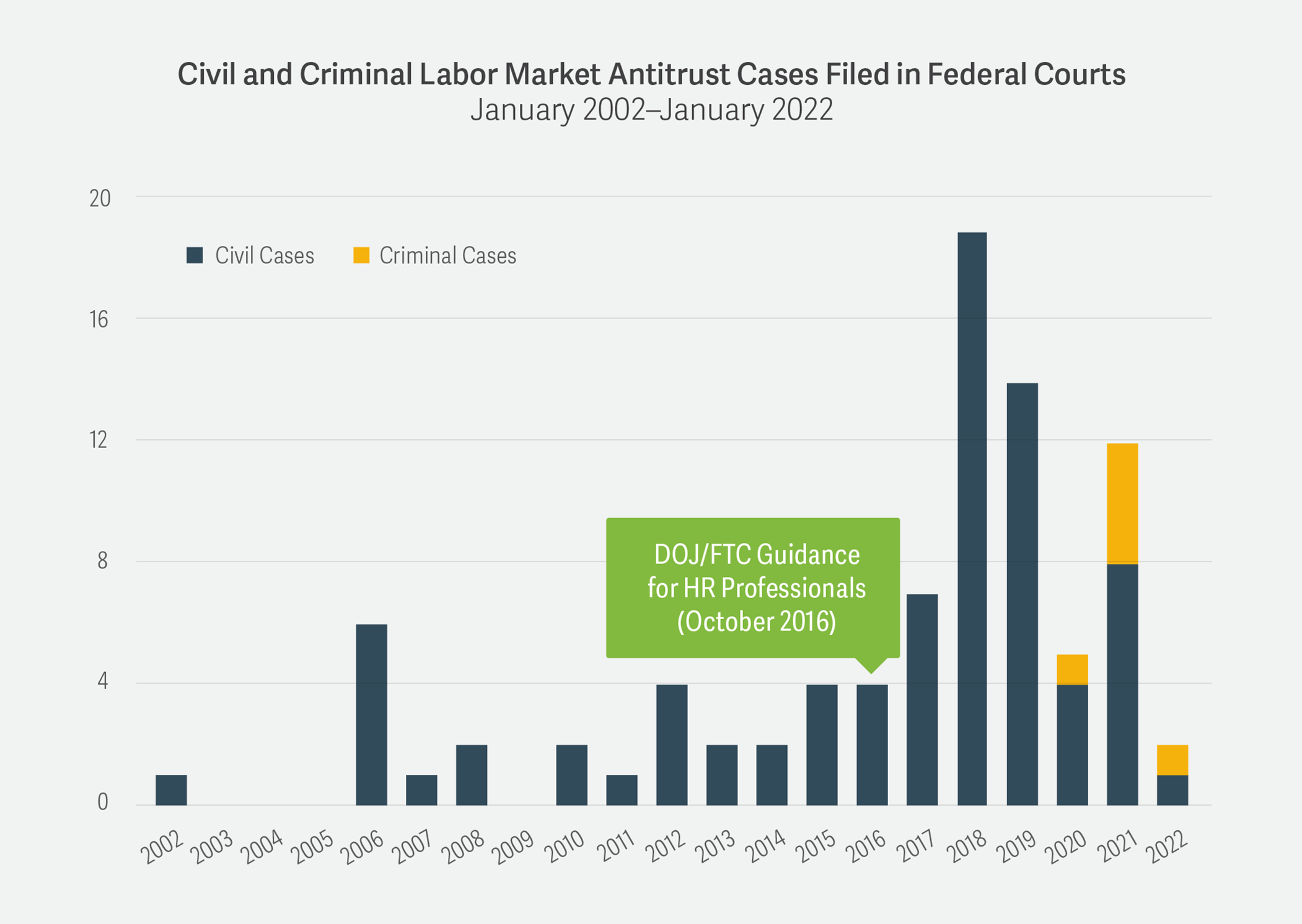

A Surge of Civil and Criminal Litigation

Not only is the new antitrust focus on labor markets clear in the enforcement agencies’ statements; it’s also borne out in litigation trends. Since the 2016 release of the Guidance, the number of labor market antitrust cases in federal courts has soared. In addition to civil litigation, these cases also include criminal actions, which had not been filed prior to 2020. The DOJ brought its first criminal wage-fixing suit, US v. Jindal, in December 2020, followed by its first criminal no-poach case, US v. DaVita Inc. and Kent Thiry, in July 2021. Analysis Group has consulted on and supported expert testimony in several of these cases.

Notes: [1] This graph includes civil and criminal antitrust cases filed in federal courts with allegations of wage-fixing, no-poach, non-solicitation, or no-hiring agreements between competitors for labor. [2] Consolidated cases are counted as a single case. Year shown in the chart represents the filing year associated with the consolidated case.

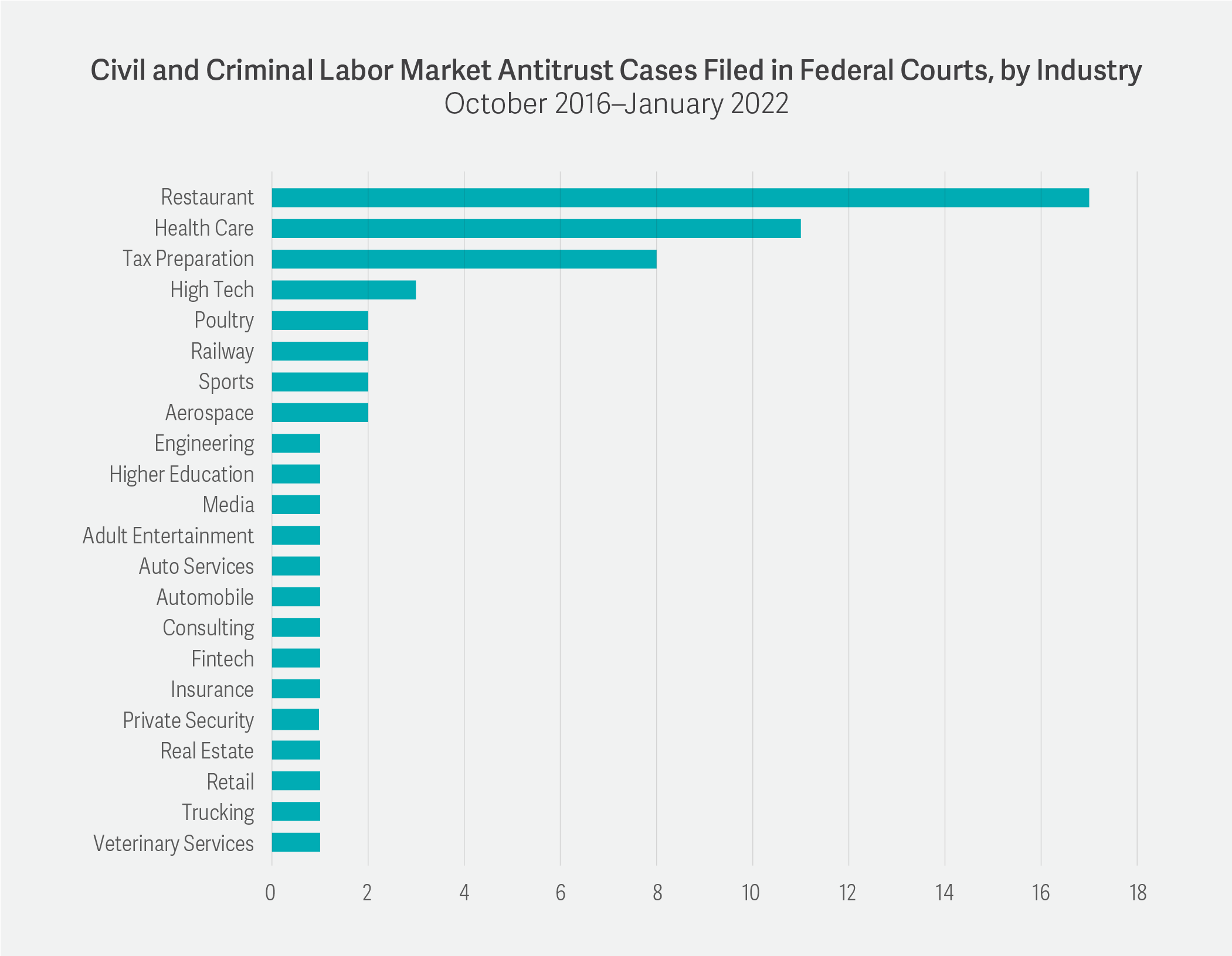

Source: Lex MachinaThis recent surge in labor antitrust litigation cuts across many industries. In particular, cases against fast food and tax preparation franchises and health care companies contributed substantially to the increase in employment antitrust litigation observed since October 2016.

Notes: [1] This graph includes civil and criminal antitrust cases filed in federal courts with allegations of wage-fixing, no-poach, non-solicitation, or no-hiring agreements between competitors for labor. [2] Consolidated cases are counted as a single case.

Source: Lex MachinaAlthough the focus on labor antitrust issues may be new, the agencies appear to be relying on standard tools and arguments, asserting that no new judicial experience or analyses are necessary to prosecute labor market conduct. The courts’ rulings on the motions to dismiss in the DOJ’s first two criminal cases – Jindal and DaVita – appear to bear this out to an extent, although certain aspects of the court’s ruling in DaVita were inconsistent with the DOJ’s push to apply traditional per se standards of proof to the case.

Jindal: Naked Price-Fixing Is Illegal, Whether in a Product or Labor Market

In Jindal, the first criminal wage-fixing case brought by the DOJ, the defendants argued in their dismissal bid that there was no precedent for bringing criminal charges over wage-fixing agreements. They noted, in particular, that “the per se rule is appropriate only after courts have had considerable experience with the type of restraint at issue.”

The Texas federal court, however, declined to dismiss the charge against the former owner of a therapist staffing company, ruling that “[t]he definition of horizontal price-fixing agreements cuts broadly” and “[a]s such, any naked agreement among competitors – whether by sellers or buyers – that fixed components that affect price meets the definition of a horizontal price-fixing agreement.” In other words, the court held that a “naked” wage-fixing conspiracy – one not reasonably related to an otherwise legitimate business arrangement – is per se illegal under the Sherman Act, just as a price-fixing agreement in the output market would be.

“The Supreme Court has made clear that the Sherman Act applies equally to all industries and markets – to sellers and buyers, to goods and services, and consequently to buyers of services – otherwise known as employers in the labor market.”– US v. Jindal (E.D. Tex., Nov. 29, 2021)

DaVita: A First Criminal No-Poach Case

In US v. DaVita Inc. and Kent Thiry, the Colorado federal court declined to dismiss the first criminal no-poach/non-solicitation case brought by the DOJ. However, the court noted that non-solicitation agreements have “rarely, if ever, been prosecuted,” and recognized that some non-solicitation agreements can be procompetitive. In its order denying the motion to dismiss, the court opined that “not […] every non-solicitation agreement or even every no-hire agreement would allocate the market and be subject to per se treatment,” and, as such, ruled that only “naked non-solicitation agreements” that “allocate the market” are subject to per se treatment under the antitrust laws.

“[H]ere, the government will have to prove more than that defendants had entered into a non-solicitation agreement – it will have to prove that the defendants intended to allocate the market as charged in the indictment.”– US v. DaVita Inc. and Kent Thiry (D. Colo., Jan. 28, 2022)

A Mixed Record

Although the Jindal and DaVita cases survived dismissal bids, the juries in both cases acquitted the defendants of all antitrust charges. A team from Analysis Group supported key economic expert testimony for the defense in DaVita. The testimony, by Analysis Group CEO Pierre Cremieux, demonstrated that DaVita employee turnover and compensation did not show evidence of labor market allocation or meaningful decrease in competition. (Dr. Cremieux spoke about his experience on the DaVita case in this Q&A.)

What Lies Ahead?

Despite significant losses in these two criminal trials, the agencies seem committed to vigorously enforcing and challenging conduct they perceive as restraining competition for labor. Following the outcomes of the Jindal and DaVita trials, the DOJ’s Kanter remarked that “[b]oth of those cases [were] extremely important cases establishing that harm to workers is an antitrust harm.” FTC Chair Khan also remained undeterred, stating that success is not “measured by a 100% court record” and that “there are huge benefits to still trying,” even if the FTC’s enforcement may be struck down as overreach.

As of May 2022, the DOJ had four criminal cases pending for alleged labor-market antitrust violations (wage-fixing, no-poach, or non-solicitation agreements), with charges against companies and individuals in the health care and aerospace industries. It remains to be seen how the Jindal and DaVita outcomes will affect these cases. What is clear is that the agencies’ statements and actions have affirmed their intention to aggressively enforce antitrust laws in the labor market. ■

-

Jee-Yeon Lehmann, Managing Principal

Federico Mantovanelli, Vice President

Rebecca Scott, Vice President

From Forum 2022.