-

Can Patent Infringement Harm Be Truly Irreparable to an Economist? A Q&A with John Jarosz and Robert Vigil

A showing of “irreparable” harm is a prerequisite in patent cases involving permanent injunctions, and it has received substantial and sensible attention accordingly. In preliminary injunction cases, irreparable harm is also a prerequisite, but it has received much less attention and been treated with much less care. Can we do better?

To explore this question, we sat down with Managing Principal John Jarosz and Principal Robert Vigil, who have testified at deposition and trial in many patent cases, prepared numerous expert reports, and coauthored a Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal article1 on the subject. Mr. Jarosz and Dr. Vigil discuss their research on patent cases in which preliminary injunctions were sought, explain why recognizing the specific meaning of irreparable harm is important, and propose a new test that they have developed to provide more consistent guidance in such cases.

How have courts assessed irreparable harm historically?

Mr. Jarosz: In 2006, the US Supreme Court issued its opinion in eBay v. MercExchange, addressing the awardability of permanent injunctive relief in patent cases. Two years later, in its opinion in Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, the court addressed the awardability of preliminary injunctive relief.

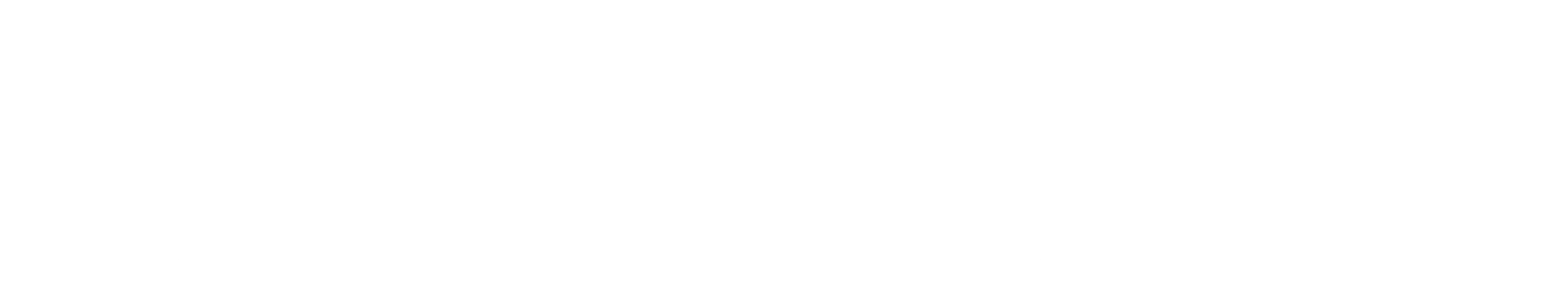

Dr. Vigil: Each case offered a four-part test. Although the eBay and Winter tests differ from one another, both require the moving party to prove that it will be irreparably harmed if an injunction is not issued.

Based on your research, when are preliminary injunctions granted in patent cases?

Mr. Jarosz: Preliminary injunctions are granted only when potentially infringing activity must be stopped while a court deliberates the merits of a patent case. By definition, a preliminary injunction is sought before a case has been argued, which makes the hurdles of the Winter test comparatively higher than those related to a permanent injunction issued as part of a merits decision. A preliminary injunction can, therefore, be a very harsh form of relief: It can end a case before it has really begun, and perhaps too early.

Dr. Vigil: Since a preliminary injunction can effectively end a case before a decision is reached on the merits of that case, courts grant them sparingly – in fact, only in about one out of three times that they are requested. Getting it right when it comes to an analysis of whether to request a preliminary injunction is of utmost importance.

Despite that, courts have not uniformly applied the four-factor Winter test [See Figure 1] when considering preliminary injunctions. Litigants are, therefore, left without clear guidance in these cases, especially concerning perhaps the least understood question in the Winter test: How do you determine if the harm is, indeed, irreparable?

Is there consistency among courts in their application of the Winter test for preliminary injunctions?

Mr. Jarosz: In short, no. In the data that we collected from 211 published district court opinions in patent cases over the years 2013 to 2020 in which preliminary injunctions were sought, there does not appear to be uniform application of the four-factor Winter test. District courts have evaluated whether the moving party prevails on the first two Winter factors – likelihood of success on the merits and irreparable harm – in every case. If the patent holder loses on either of those factors, an injunction will not be issued.

After evaluating the first two Winter factors, many district courts have not gone on to evaluate the second two factors – balance of the equities and public interest – often leaving an incomplete record for appeal purposes.

Dr. Vigil: Of the 211 cases that we examined, the court only offered an opinion on all four Winter factors in 108, or about half of those cases. For the other 103 cases, the court did not provide an opinion on all four factors, almost entirely because the patent owner did not prevail on the first two Winter factors.

In fact, in all 59 of the cases in which a preliminary injunction was granted, patent owners had shown both that they were likely to succeed on the merits and that they would suffer irreparable harm without an injunction.

But in 10 of those cases, courts granted preliminary injunctions even though they did not explicitly find balance of the equities or public interest factors to favor the plaintiffs.

“Assessing what harm is irreparable is not a straightforward exercise, and courts have conflicting opinions on the subject...The resulting lack of clarity for litigants can lead to increases in the costs of litigation, as well as decreases in certainty over whether a request for a preliminary injunction is likely to succeed.”– John Jarosz

How is irreparable harm distinct from simply “harm” in this context?

Mr. Jarosz: Assessing what harm is irreparable is not a straightforward exercise, and courts have conflicting opinions on the subject. In our research, we found that some courts have used measures of patent owner outputs, like sales, market shares, and prices (sometimes too loosely, sometimes too rigidly); some have used measures of patent owner inputs, like research and development and employment (sometimes too loosely, sometimes too rigidly); and some have considered factors that are not forms of harm at all, like delay in filing suit.

The resulting lack of clarity for litigants can lead to increases in the costs of litigation, as well as decreases in certainty over whether a request for a preliminary injunction is likely to succeed.

Dr. Vigil: Uncertainties regarding the bounds of what is to be deemed irreparable harm may increase the likelihood of an uneven playing field where certain meritorious claims will not prevail and certain non-meritorious claims will. It may also increase the likelihood that certain credible cases will not be pursued and some less deserving cases will be.

What can litigants do to guard against such unpredictability?

Mr. Jarosz: They could adopt one test and apply it sensibly across cases, time, and courts.

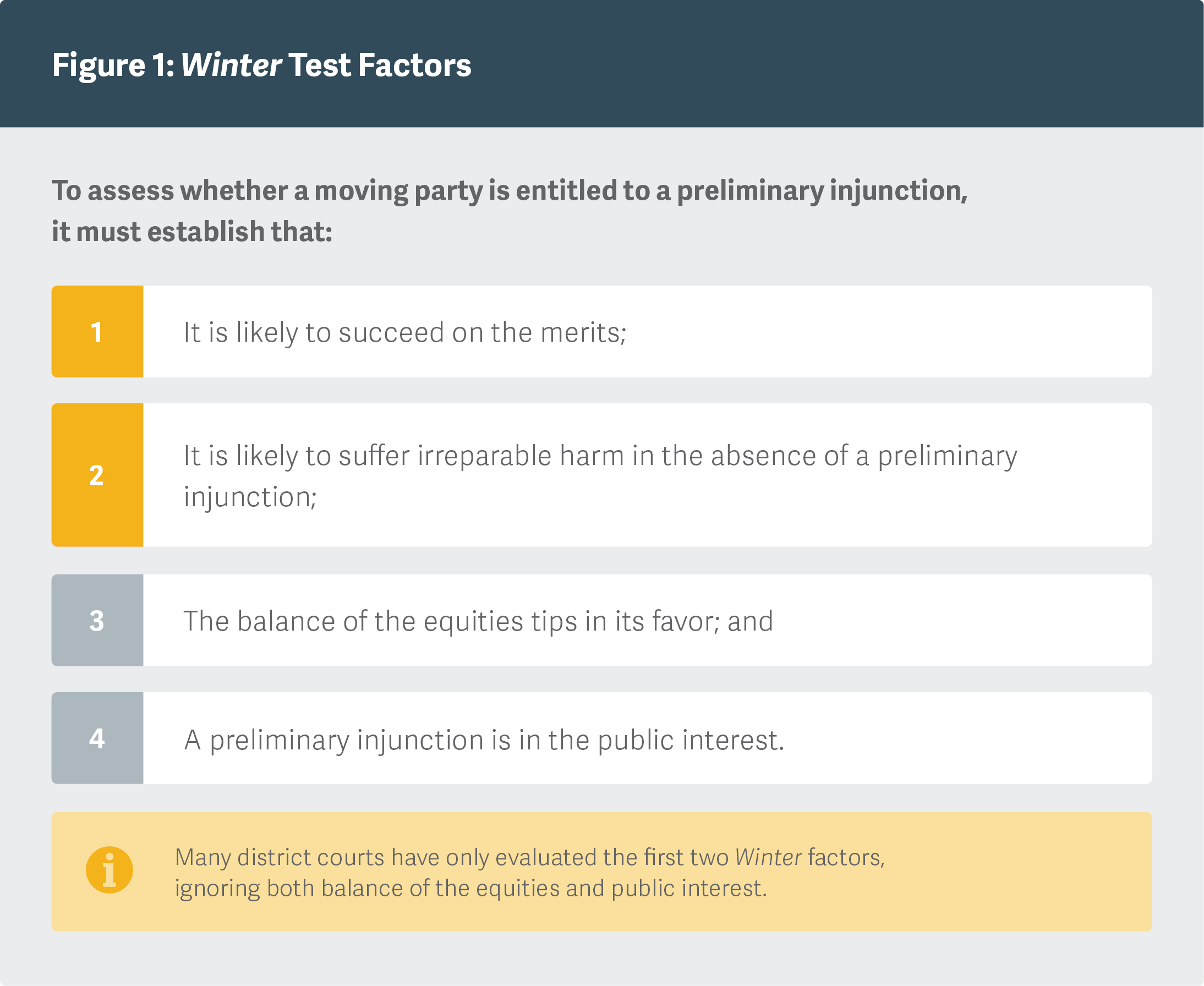

Dr. Vigil: Since irreparable harm has proven to be one of the most important Winter factors, we propose a new test to systematically define what harm is irreparable.

What is your proposed test?

Mr. Jarosz: Our proposed test [See Figure 2] addresses several factors that could be considered determinative when assessing whether such harm warrants a preliminary injunction. We propose that for harm to be deemed irreparable, it must first be shown to disrupt the status quo – that is, it must make a meaningful difference. Second, the harm must be imminent and likely to occur, as opposed to being merely theoretical or potential. Third, it must be causally linked to the alleged infringement. Finally, there must be reasonable economic certainty that the patent owner either cannot or will not be adequately compensated or made whole by other means, such as the assessment of damages.

Dr. Vigil: We believe this four-part test, which is grounded in economics, can be used to add more certainty and predictability for litigating parties.

Is there anything else that litigators should keep in mind if they attempt to employ this test?

Mr. Jarosz: There is quite a bit of nuance to be considered in each of the factors of this test. Every element may involve the contemplation of multiple sub-factors and facts. Failure to fully consider these factors could lead to serious consequences.

Litigators should remember that proving irreparable harm is a necessary condition for a court to grant a preliminary injunction and that such rulings can effectively end a case without a discussion of its merits. They should also keep in mind that irreparable harm is not the same as harm. While experienced economists may be consulted when quantifying either kind of harm, run-of-the-mill harm often is more readily quantifiable. Understanding irreparable harm requires a different, more nuanced approach.

Dr. Vigil: Whether a preliminary injunction is granted can have profound effects on a litigation. That, in combination with the complexity of an analysis of irreparable harm, establishes the need for a systematic approach like ours to define such harm. ■

Endnote- Jarosz, John C., Jorge L. Contreras, and Robert L. Vigil, “Preliminary Injunctive Relief in Patent Cases: Repairing Irreparable Harm,” Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal, vol. 31, pp. 63–130 (2023).

From Forum 2023.