-

The Biosimilar Revolution Is Just Beginning in the US

The age of biologics is upon us. These medicines are “grown” biologically, rather than manufactured chemically.

In terms of total US revenue, 7 of the top 10 drugs in 2015 were biologics, including such blockbusters as Humira, Enbrel, Rituxan, and Herceptin.

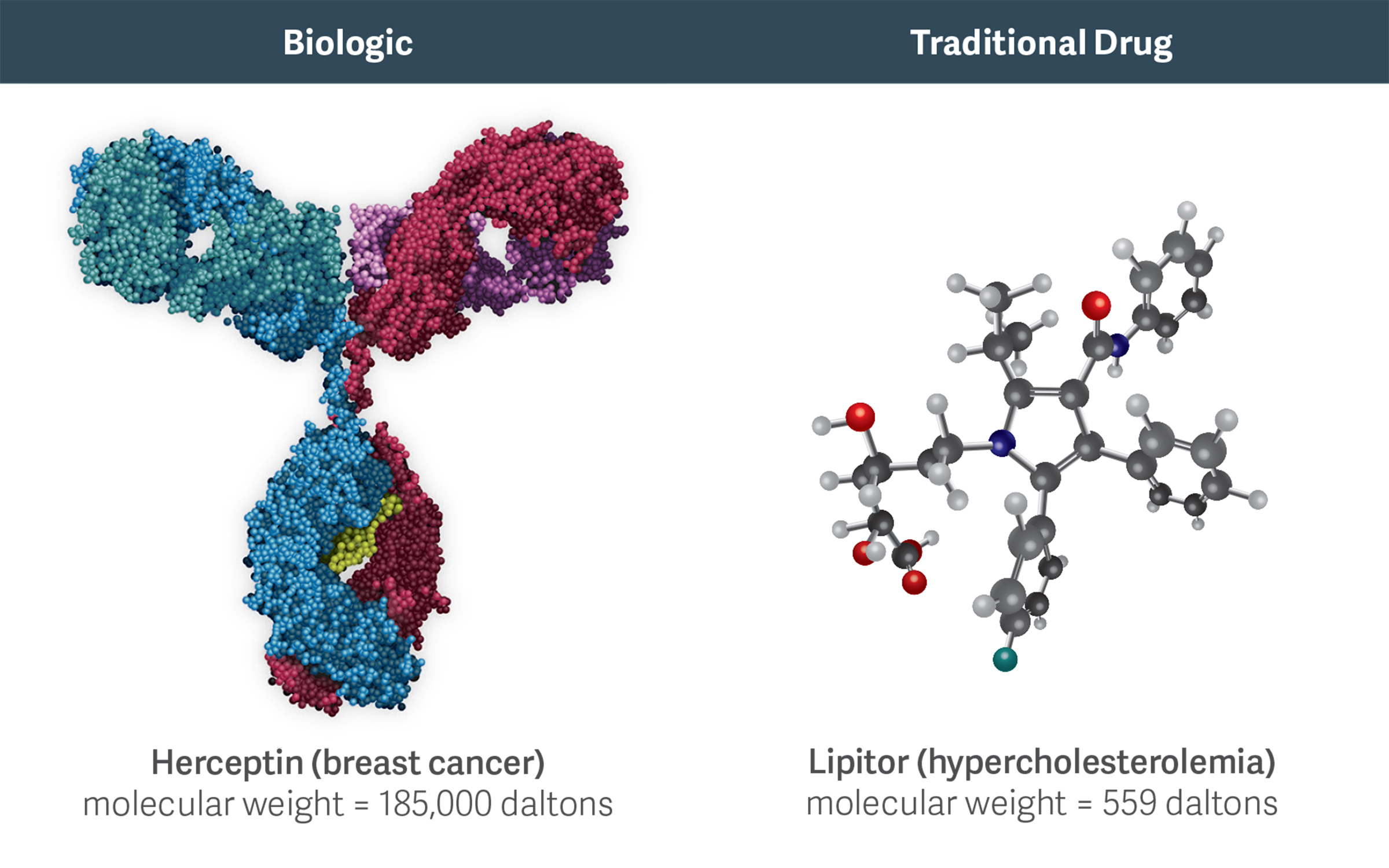

High-molecular-weight biologics like Herceptin are more complex than traditional, small-molecule chemical drugs like Lipitor. This complexity increases the costs, challenges, and risks of developing and manufacturing biosimilars.

Biosimilars are drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon demonstrating similarity to a branded biologic. They are akin to generic drugs, which are approved based on demonstrating equivalence to a branded small-molecule drug. While entry of biosimilars to the US market is still in its infancy, their potential for widespread introduction represents one of the most significant events to impact the drug industry in decades, with many top-selling biologic drugs expected to be affected over the next few years. The impact of biosimilars on the competitive landscape is also likely to include an evolving mix of related litigation.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 paved the way for biosimilar entry, and the FDA Biosimilar Product Development Program currently includes more than 50 biosimilars, referencing more than 15 different innovative biologics. To date, five of those biosimilars have been approved:

- Zarxio (brand reference product Neupogen) in March 2015

- Inflectra (brand reference product Remicade) in April 2016

- Erelzi (brand reference product Enbrel) in August 2016

- Amjevita (brand reference product Humira) in September 2016

- Renflexis (brand reference product Remicade) in April 2017

The global market for biologic drugs has been forecast to exceed $390 billion annually by 2020, and some analysts predict substantial cost savings after more biosimilars are approved and introduced, as was the case with the introduction of generics.

Greater Complexity and Unique Regulations Lead to Economic Challenges

Indeed, one goal of the BPCIA was to achieve substantial cost savings, resembling those realized from the widespread adoption of generics. However, the development and approval processes for biosimilars, which are large-molecule biologics, are very different from those for generics, which are small-molecule chemical drugs. One reason for the difference from generics is that biologic drugs are substantially more complex than small-molecule drugs, as they are derived from living organisms. (See figure.)

Such complexity has the potential to introduce more variability into the development and production of biosimilars, as compared with generics. This reality is reflected in current FDA approval requirements. For example, the FDA requires costly Phase III trials to approve a biosimilar. Once approved, manufacturers must use distinct brand-like names for their biosimilars. In addition, approved biosimilars are currently not considered “equivalent” to the originator by the FDA. Taken together, these differences can greatly increase the costs and risks associated with developing, producing, and marketing biosimilars.

In fact, these high costs are likely to limit entry to a relatively small number of competitors, in contrast to the experience with small-molecule generics. And the uptake of any approved products may well be tempered, as they are unlikely to benefit from state substitution laws and payer mechanisms that would encourage switching between the innovator and the biosimilar.

Consequently, biosimilar competition may share more features with traditional brand-brand drug competition than with brand-generic competition. Indeed, the limited experience of biosimilar entries to date reveals penetration rates that are much more modest than for generics, coupled with substantially smaller price discounts. (See table.)

As a result of all these factors, we expect biosimilar adoption to be more gradual than has been seen with the rapid shift to generics for many small-molecule drugs.

An Evolving Landscape

These economic considerations will figure prominently in manufacturers’ decisions and damages disputes in litigation involving biosimilars and their innovator counterparts. And, litigation in this context is likely to be wide-ranging – from patent disputes and antitrust allegations that have characterized generic entry, to product safety lawsuits and allegations of improper or misleading promotion. Understanding how competition will play out as additional biosimilars are introduced to the US marketplace will be key to assessing damages correctly in these cases. ■

Comparison of US Biosimilar and Generic Drug Average Share of Sales and Price Discount (Six Months After Launch) Share of sales

vs. originatorPrice discount

vs. originator*Generic Drug Average ≥75% ≥40% Zarxio (biosimilar Neupogen) ~10% 15% Granix (quasi-biosimilar Neupogen) 5-10% ~11-23% * Public price (e.g., WAC), not including contracted discounts/rebates

Source: Generic drug average: Berndt et al., Health Affairs, 26, no. 3 (2007); Grabowski et al., Journal of Medical Economics (2016). Zarxio and Granix: Publicly available data.

Paul E. Greenberg, Managing Principal

Richard A. Mortimer, Managing Principal

Alan G. White, Managing Principal

Tamar Sisitsky, Senior AdvisorAdapted from “Can The Life Sciences Industry Bank On Biosimilars?” by Paul E. Greenberg, Tamar Sisitsky, and Richard A. Mortimer, published on Law360.com, April 13, 2016; and “The Potential For Litigation In New Era Of Biosimilars,” by Christian Frois, Richard A. Mortimer, and Alan G. White, published on Law360.com, September 20, 2016.