-

Taxing Questions: Managing the Taxation Complexities of Smart Contracts

In their efforts to maintain competitiveness, multinational businesses are increasingly adopting innovative technologies and digitalized processes.

The digital economy is raising new questions about tax oversight and compliance. Business managers and regulators alike are exploring ways to reap the benefits of digitalization while minimizing potential transaction inefficiencies that may be associated with them. As part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) initiative, OECD member countries have been actively addressing the challenges of developing “actionable, global tax planning solutions” against the backdrop of the growing digitalization of the global economy. Earlier this year, a report issued by the OECD noted, “These challenges chiefly relate to the question of how taxing rights on income generated from cross-border activities in the digital age should be allocated among countries.”1

The use of blockchain technology to enable smart contracts is one example of digitalized processes introducing additional complexity into tax governance, even for non-digital businesses. Understanding how smart contracts create value will be fundamental to ensuring that tax authorities avoid creating a mismatch between where value is created and where profits are taxed.

What are smart contracts?

Smart contracts are decentralized, anonymized, blockchain-coded agreements that facilitate the automatic exchange of cryptocurrencies (e.g., Bitcoin) or tokens (e.g., Ether) for goods or services. When the preprogrammed terms and conditions of an agreement are met – for example, when placing an order – the smart contract executes automatically. If set up correctly, the system can verify valid transactions more securely and identify fraudulent transactions more easily. These advantages are critical, since a single smart contract can have thousands of anonymous transactions associated with it, all triggered by digital activity.

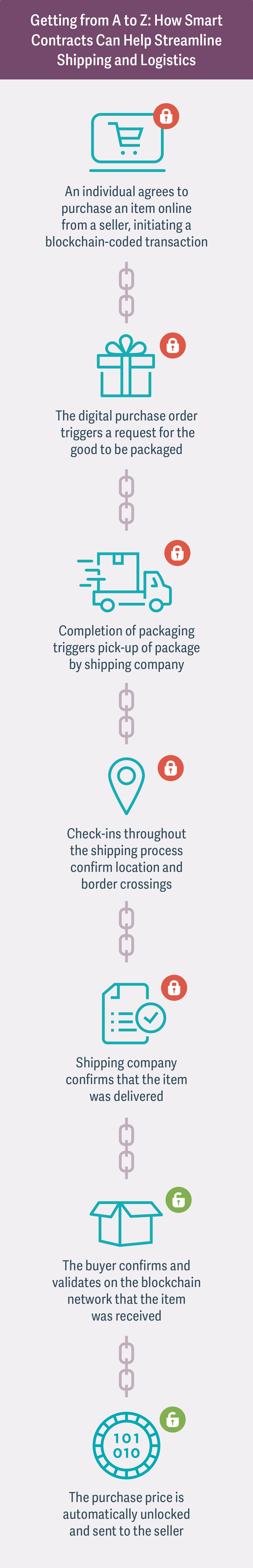

In one real-world application of a smart contract, international transportation logistics companies are exploring new applications for blockchain-based systems. They are working to code virtual shipping agreements that digitally track the purchase of, payment for, transport of, and actual receipt of a good that is physically delivered to an end customer. These companies are looking to smart contracts to improve the security of the payment process and decrease the potential for fraud in online transactions and ultimate delivery of the good. These new types of agreements may change transaction processes as we know them – for instance, by unlocking payment only when the delivery is confirmed as received. (See figure.)

However, smart contracts also raise complex taxation and regulation issues. The underlying transaction in which the cryptocurrency is exchanged for goods or services may result in taxation at many different levels. It may not always be clear what type of tax is relevant, and in which tax jurisdiction any given tax must be paid – a particularly important question with borderless, global markets. This concern is heightened if tax authorities are not part of the blockchain network. The closed nature of the transaction processing, as well as the use of cryptocurrencies as the medium of exchange, can make it more difficult to ensure that the appropriate taxes and duties are being charged and collected on international shipments.

Taxing the sale of products or services

For example, as shown in the figure, two parties could enter into a smart contract in which the buyer agrees to pay X Ether to the seller in exchange for Good Y. Once Good Y is delivered (and verified by the decentralized blockchain network, through the process of “mining”), X Ether are sent to the seller – all automatically, via the digital platform. In this way, the smart contract ensures that the same secure, unalterable data string identifying that specific transaction is used by both the buyer and the seller to confirm ordering, packaging, shipping, delivery, and payment – without the need for paperwork or the intervention of financial intermediaries, such as banks or credit card companies.

In these cases, because the blockchain exchange happens automatically and anonymously, tax authorities may have to rely solely on the seller to collect and report sales tax on all transactions. However, questions of where in the transaction chain value is actually created and captured can lead to debate about the appropriate tax jurisdiction. This can lead to uncertainty among platform users about their tax liabilities – including whether the activity is taxable at all – and potentially result in under-reporting or jurisdictional disputes.

Regulating smart contracts: Weighing the costs and benefits

Understanding how smart contracts create value is fundamental to ensuring that tax authorities respond appropriately to these challenges. The question of economic nexus – determination of the jurisdiction where economic activity, or value creation, takes place – has significant implications for tax burden. It will benefit all parties involved if the costs of monitoring and auditing blockchain transactions for tax purposes are balanced with the convenience and low intermediary cost associated with them. ■

NotesNotes

- “Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalisation of the Economy,” OECD Public Consultation Document, February 13–March 6, 2019, available at: https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/public-consultation-document-addressing-the-tax-challenges-of-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy.pdf.

Jimmy Royer, Principal

Alan G. White, Managing PrincipalAdapted from “Smart Contracts & Their Potential Tax Implications” by Jimmy Royer and Alan G. White, Lawyer Monthly, October 2018.