-

Making the Right Call: SOM for Prescription Opioids

As the opioid crisis continues, the Suspicious Order Monitoring (SOM) requirement has become an increasingly important enforcement tool for the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

This regulatory clause, which dates back to changes to the 1970 Controlled Substances Act (CSA) enacted in 1971, requires any DEA-registered entity distributing opioids or other controlled substances to “design and operate a system to disclose ... suspicious orders of controlled substances.” Suspicious orders are defined as “orders of unusual size, orders deviating substantially from a normal pattern, and orders of unusual frequency.”

However, the DEA has provided little guidance beyond these words in the nearly 50 years since the clause’s enactment. Most recently, the DEA’s position in cases involving wholesale distributors reveals that the agency has set a high bar for monitoring orders of controlled substances – particularly in terms of making use of available data. In the DC Court of Appeals ruling involving Masters Pharmaceutical in early 2017, for example, the court found that the DEA was within its rights to revoke Masters’ controlled substance license due to failures to comply with the SOM requirement. Like many pharmaceutical distributors, Masters employed a statistical algorithm to make an initial screen of pharmacy orders. Masters then selected a subset of the orders flagged by the algorithm and subjected them to manual review. Following the manual review, Masters would report suspicious orders to the DEA.

One of the key points of contention in the case was whether Masters’ algorithm and review process appropriately used all available data and analytics to determine which orders to report. Although the SOM statute defines suspicious orders in terms of size, pattern, and frequency, the Masters decision emphasizes that these are not an exhaustive list of criteria. Other red flags include, for example, the relative volumes of controlled and non-controlled substances, as well as mismatches between ordering and actual dispensing at the pharmacy. However, data on dispensing are not generally available to distributors in the regular course of business.

The DEA administrator’s original decision in Masters states that “a distributor is required to use the most accurate information available.” What constitutes availability, however, is not straightforward and gives rise to questions about the DEA’s application of the standard.

In some cases, Masters’ manual review process for orders flagged by the algorithm involved obtaining additional pharmacy utilization data to assess the proportion of prescriptions attributable to controlled substances. However, in other instances, additional data of this type were not obtained. According to the court, this selective approach was inadequate in analyzing additional data beyond size, pattern, and frequency.

Accuracy Is Critical, but Involves Important Tradeoffs

The court underscores the perception that the bar to dispel the possibility of suspicion for a flagged order is high. While Masters viewed the orders initially flagged only as potentially suspicious, the decision rejects this approach, indicating that any orders flagged by an algorithm should be considered suspicious unless otherwise dispelled. Given the derivative requirements to block and report suspicious orders, there is a gulf between “potentially suspicious” and “suspicious” that may be as wide as that between “innocent until proven guilty” (or arrested and awaiting trial) and “guilty until proven innocent” (or convicted, pending appeal).

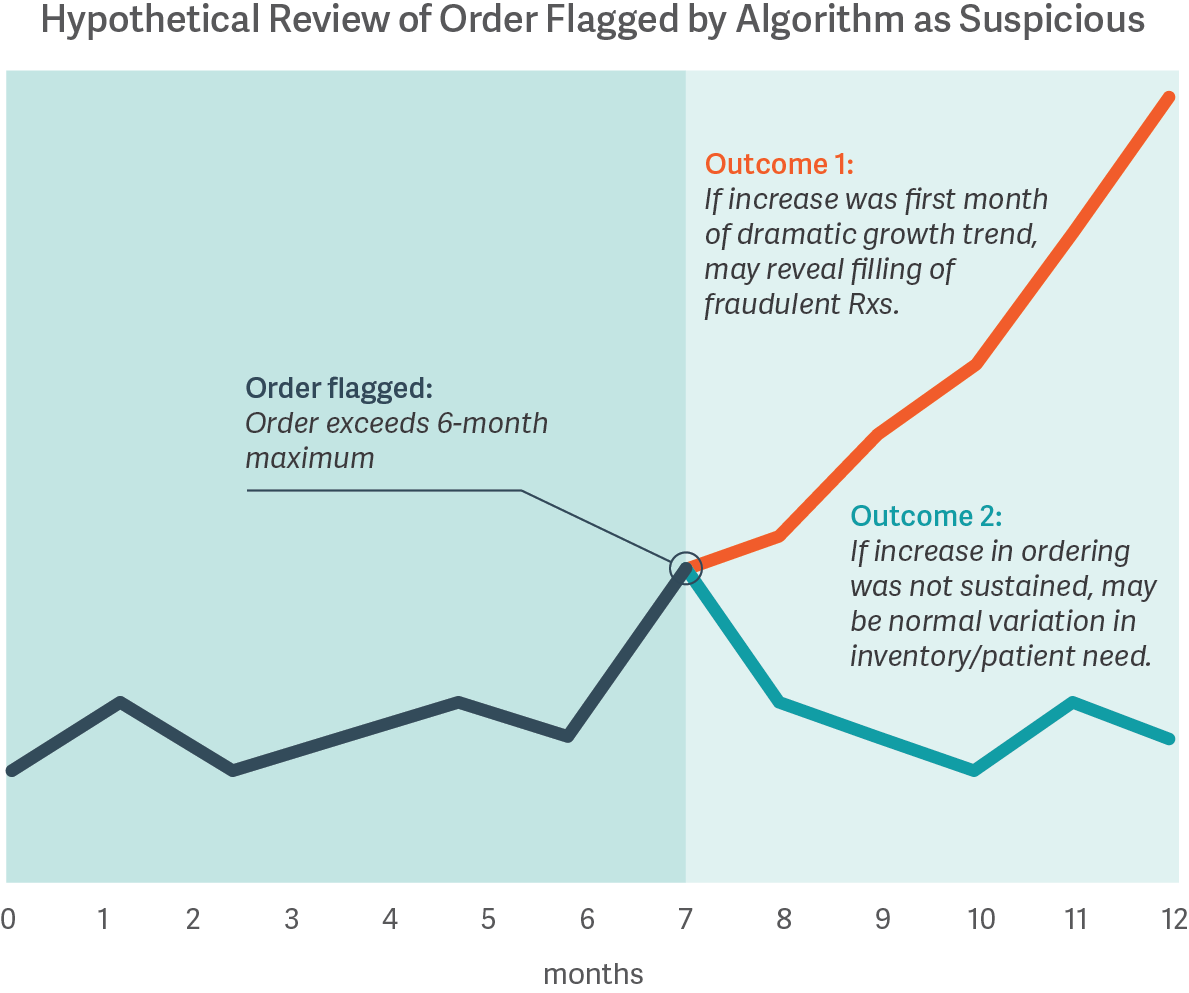

The costs of misclassifying orders are high, whether a distributor is blocking legitimate orders meeting patient needs or is fulfilling orders to pharmacies later found to have illegitimate activity. However, no algorithm or review process is guaranteed to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate activity; some improper dispensing can only be identified with certainty based on hindsight. For example, the figure below shows how an order initially may be flagged by a statistical algorithm based on a customer’s prior history, and only with the benefit of hindsight does the presence or absence of illegitimate dispensing become clear.

While it may be possible to calibrate a statistical approach based on analysis of pharmacies known to have had illegitimate dispensing in the past, data on such pharmacies are often limited. Moreover, there is no ex ante guarantee that such an approach will reliably identify the next issue, nor that the resulting algorithm will appropriately filter out legitimate activity. Thus, pharmaceutical distributors must operate with incomplete information, as certain types of data may never be available until well after the fact.

Nonetheless, given the high cost of imprecision, distributors should strive to make the best use of the data that are available to them, keeping up with current trends to avoid an overly backward-looking approach. They should also carefully consider the balance between sensitivity and specificity.

A highly sensitive algorithm will cast a wide net and will be unlikely to miss any genuinely suspicious activity, but it will also flag many orders that are not unusual. With an overly sensitive system, a distributor that blocks and reports all orders could easily put legitimate patient needs in jeopardy. Because human reviewers may become ineffective if they are reviewing a large number of orders that were flagged unnecessarily, a distributor may decide that it is safer not to rely on manual review at all and end up over-reporting suspicious orders to the authorities, which does not advance the cause.

Conversely, a highly specific algorithm will have a larger share of its flagged orders that prove to be of genuine concern, but may miss others. In this scenario, review of flagged orders will be more efficient than with an overly sensitive system. But that could also come at a high cost, as some illegitimate orders may not be identified.

Maintain Consistency, but Make Improvements

The Masters decision stresses the importance of consistency in the review process. Absent explicit regulatory guidance on the SOM requirement, internal consistency may act as the most straightforward standard. The decision found that Masters’ review process was inconsistent across orders and conflicted with the approach laid out in its own compliance documentation.

At one extreme, Masters could simply have blocked and reported every order flagged by its algorithm. However, this approach would certainly have blocked many legitimate orders. Consistency requires ongoing efforts to monitor the review process and regularly obtain additional data. Setting up standard reports with key data analytics pertaining to flagged orders can make the manual review process more systematic and less ad hoc. Maintaining consistency may also require periodic modifications to the statistical algorithm to incorporate analyses that are repeatedly identified as part of manual review.

Distributors who are not inclined to incorporate manual review into their SOM may still want to minimize risk by setting up efficient statistical tools tailored to their customer base to comply with the Effective Controls Against Diversion requirement.

With SOM being featured as a critical plank in the DEA’s approach to countering the opioid crisis, distributors will need to make increased efforts to meet these requirements. Limited guidance, the lack of sufficient data for calibration, and incomplete customer information present real challenges. Even with carefully thought-through statistics and well-trained reviewers, the decision of whether to report an individual order is difficult to systematize. The principles discussed above can help inform those decisions by providing a sound combination of statistics and judgment. ■

Crystal Pike, Managing Principal

Kenneth Weinstein, Managing Principal

Nicolas Van Niel, Vice PresidentAdapted from “A New Standard for Suspicious Order Monitoring: Part 1,” by Crystal Pike, Kenneth Weinstein, and Nicholas Van Niel, published on Law360.com, August 21, 2017.

Related article in this issue: “ Abuse-Deterrent Opioids and the Economic Costs of Abuse ”