-

Numerosity, Ascertainability, and Causation: Navigating Class Claims of Alleged Delayed Generic Entry

The outcome of a case involving the blockbuster statin Lipitor shows that plaintiffs can face scrutiny from the Court before certifying classes when bringing antitrust claims against pharmaceutical industry defendants.

Class actions involving allegations of delayed generic entry can result in claims for billions of dollars in damages against branded and generic drug companies. The decade-long In re: Lipitor Antitrust Litigation is an example of a dispute that involved such claims. To respond to the plaintiffs’ allegations, the Lipitor defendants prepared a rigorous, fact-based rebuttal that incorporated economic analysis at the class certification and summary judgment stage of the case.

In Lipitor, the plaintiffs alleged that the settlement of a patent litigation between Pfizer and Ranbaxy delayed the entry of the generic formulation of Pfizer’s blockbuster cholesterol treatment Lipitor (atorvastatin). Alleging that the settlement was anticompetitive, the plaintiffs asserted that the defendants’ conduct forced drug wholesalers, pharmacies, health plans, and consumers to pay billions of dollars in overcharges for Pfizer’s branded version of the statin.

The plaintiffs attempted to certify classes of atorvastatin purchasers in connection with the suit. For that to happen, however, such classes must meet the requirements of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The inability to satisfy three of those requirements – numerosity, ascertainability, and causation – felled the plaintiffs’ certification arguments in Lipitor and supported a US District Court judge’s grant of summary judgment to the defendants in the long-running matter. For their part, the defendants brought significant factual evidence to rebut the plaintiffs’ attempts to define each class, identify class members, and establish common proof of injury.

The Lipitor judge released three separate opinions – quoting each of the three testifying experts supported by Analysis Group in the case – to show that the Court would not certify classes that depend on speculative approaches to Rule 23’s numerosity, ascertainability, and causation requirements. These opinions highlight the key issues the Court considers when certifying a class.

Below, we briefly summarize those requirements, explore litigants’ arguments related to each requirement in this case, examine the opinions of the Lipitor judge on each issue, and assess how the testimony of Analysis Group experts factored into the Court’s decision making.

Numerosity

Among other things, Rule 23 requires that certified classes meet a minimum size requirement that is “so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable [i.e., difficult].”

Plaintiffs’ Allegations: Drug wholesalers and pharmacies who purchased atorvastatin directly from manufacturers sought to certify a class of plaintiffs, arguing “that joinder is impracticable given the class size, judicial economy, and the geographic dispersion of the class.”

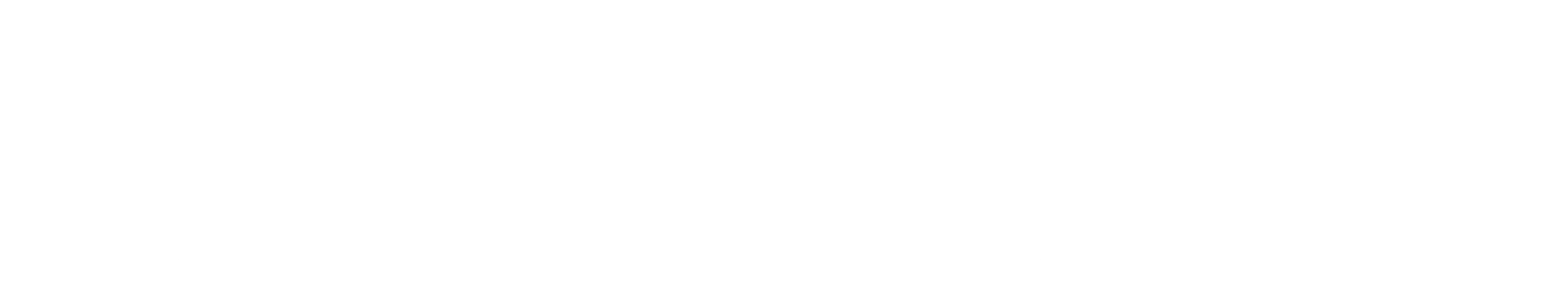

Ruling: Following an analysis of the Modafinil impracticability factors, citation of several similar cases (including Value Drug Company v. Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., et al.), and testimony from Analysis Group expert Bruce E. Stangle, the judge ruled that the plaintiffs did not satisfy their burden to demonstrate that joinder is impracticable.

Explanation: Satisfying numerosity requires showing that class members’ ability and motivation to litigate as joined plaintiffs is impaired. In ruling on the Modafinil impracticability factors, the judge noted that the plaintiffs have a history of cooperation, even entering merger agreements with each other. The judge was also concerned about certifying a class with three plaintiffs having 91 percent of the total claims.

Expert Citation: The Court quoted Dr. Stangle on the subject of the second Modafinil factor (claimant’s ability and motivation to be joined), agreeing with his assessment that several mergers between the class members over a broad period suggest that “the incentives for cooperation among the proposed class members have existed and continue to be present.”

Ascertainability

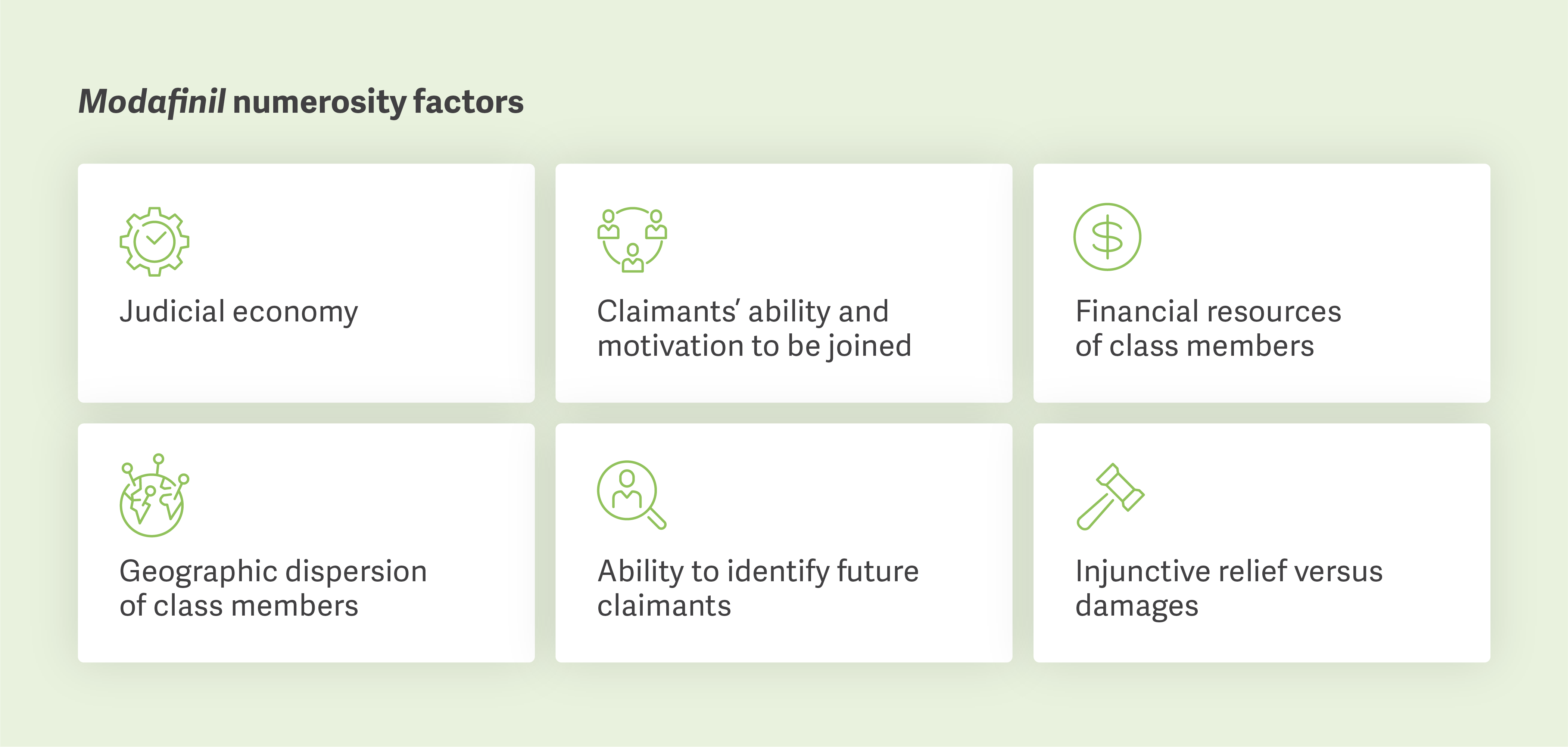

The Court wrote that “to satisfy the ascertainability requirement, a plaintiff must present a methodology to identify class members and prove by a preponderance of the evidence that such methodology will not require extensive or individualized inquiry or mini-trials.”

Plaintiffs’ Allegations: The plaintiffs sought to certify both a consumer class and a third-party payer class on the basis that those classes would conform with Rule 23’s ascertainability requirement.

Ruling: The Court questioned whether the plaintiffs had established a reliable methodology to identify class members. It followed precedent set forth in the In re: Niaspan Antitrust Litigation in its analysis.

Explanation: Although the plaintiffs’ expert offered criteria to identify class members, they did not demonstrate any verification method, let alone an administratively or financially feasible one. Instead, the plaintiffs only suggested that data available from outside parties (e.g., third-party payers, pharmacy benefit managers, health plans, and governmental entities) could be used to determine who belonged to the proposed classes.

Expert Citation: The judge quoted Analysis Group expert James W. Hughes in his opinion. Professor Hughes testified that, “[The opposing expert] says the data are available from a number of sources to verify class membership. This is not methodology, it’s not a system, not a set of steps that one would go through to identify the class members.”

Causation

Inextricable from the plaintiffs’ claims of class-wide injury is their assertion that economic damages were caused by the actions of the defendants.

Plaintiffs’ Allegations: The plaintiffs claimed that they were subject to overcharges for the purchase of atorvastatin because of an allegedly anticompetitive settlement agreement between the defendants to delay generic entry of Lipitor. They argued that the agreement effectively extended Pfizer’s market exclusivity for the statin, which allegedly led to plaintiffs paying overcharges.

Further Claims: They also claimed that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would have approved Ranbaxy’s atorvastatin generic sooner, but for the existence of the at-issue agreement: “[H]ad Ranbaxy agreed to an earlier entry date with Pfizer, FDA would have targeted an earlier date to complete review of Ranbaxy’s Lipitor.”

Ruling: The Court ruled that there was no evidence to support the plaintiffs’ claim that the FDA’s decision was delayed because of the at-issue settlement and stated that “regulatory requirements in this case obstruct plaintiffs’ argument that FDA would have moved quicker,” absent the settlement. As such, the Court agreed with the defendants’ contention that the plaintiffs “failed to create a genuine issue of material fact that it was more likely than not that FDA would have completed its review any sooner and approved Ranbaxy's generic drug manufacturer's ANDA [Abbreviated New Drug Application] earlier than November 30, 2011—even by one day.”

Explanation: Since no link between a delay in FDA’s approval processes and the settlement could be proven by the proffered evidence, the Court granted summary judgement to the defendants, citing a lack of causation and mirroring the logic of the decision in the Wellbutrin XL Antitrust Litigation.

Further Explanation: The FDA showed that it was committed to a comprehensive and careful review of Ranbaxy’s application to market generic atorvastatin. The most pertinent example of the FDA’s adherence to its own strict standards for review is the agency’s issuance of its Application Integrity Policy (AIP) to Ranbaxy for failure to comply with regulatory standards for drug manufacturing. The AIP is a mechanism that stalls the review of any ANDA and requires a restart of the same, once it has been resolved or excepted.

Expert Citation: The Court quoted former FDA Chief Counsel Dan Troy – who was supported by Analysis Group – on the rarity of the AIP, “The AIP is an exceptional and rarely used program, intended only for the most severe cases of noncompliance.” Mr. Troy concluded that once the AIP was overcome, the main elements of the Ranbaxy Lipitor ANDA would need to be reviewed again, from scratch, thereby creating a natural delay in FDA’s processes once the AIP was invoked. The Court also cited Mr. Troy’s examples of FDA’s review of other ANDAs for blockbuster drugs that were not approved by the earliest target date, stating that “[t]hese examples hammer home the fact that FDA is not glued to meeting earliest possible entry dates and will not achieve an earlier entry date merely to achieve a target date put forth by pharmaceutical manufacturers.”

Court Citation: Mr. Troy’s assessment played a role in the Court’s opinion that “the elements of the Ranbaxy Lipitor ANDA process were so unusual ‘they could not have been anticipated’ ... FDA was targeting a date. A target date does not equal a guarantee or even raise the likelihood that, more likely than not, FDA would have approved Ranbaxy’s Lipitor ANDA any faster.”

Antitrust class action litigations involving allegations of delayed generic entry are frequently brought to courts and are likely to remain a feature of the pharmaceutical landscape. As in Lipitor, understanding whether the claims of those proposed classes meet the high burden of proof for class certification set forth in Rule 23 can depend on a specific, fact-intensive review of the at-issue evidence in each case. Economic expert testimony can assist courts in such a review, helping to clear the way for a favorable resolution. ■

Ted Davis, Managing Principal

Jonathan Baker, Vice President

Mark Berberian, Vice President

Dylan Kellachan, Vice President

Brendan Rogers, Vice President

This feature was published in February 2025.