-

Examining Trends in Drug Development: A Q&A with Michael Kinch

Assessing the risks involved at each phase of clinical testing and the likelihood that a drug in development could overcome regulatory hurdles to obtain FDA approval are critical considerations for investors, entrepreneurs, and other decision makers in life sciences. These assessments are also often the subject of expert analysis in litigation matters involving product valuations and development efforts.

To explore trends in drug development and industry factors impacting risks and successes of R&D in life sciences, Managing Principals Jee-Yeon Lehmann and Stephen Fink spoke with academic affiliate Michael Scott Kinch of Long Island University. In this conversation, Professor Kinch addressed trends in the clinical development and approval process, how that process may differ across certain types of drugs, and potential implications of these trends for emerging treatments.

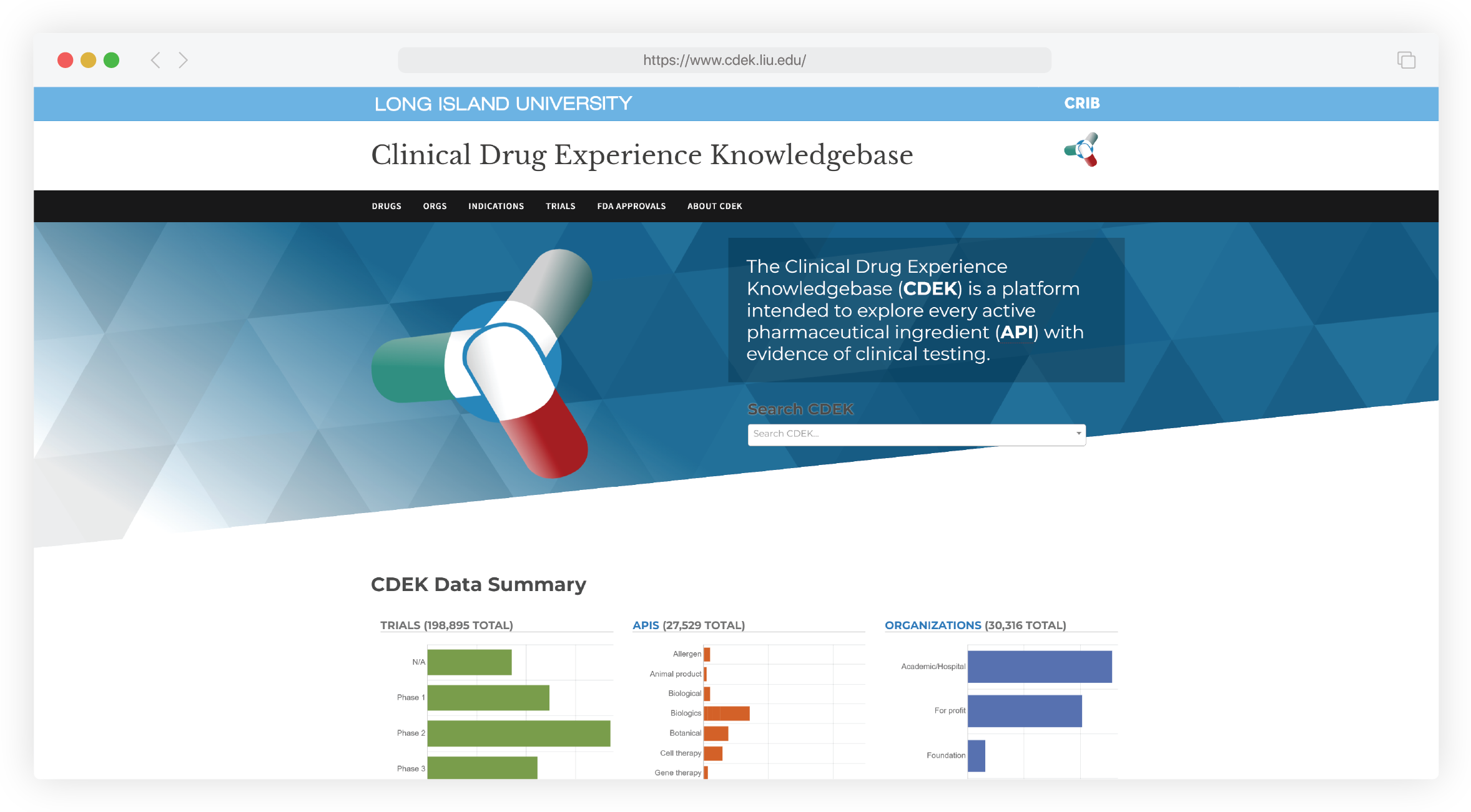

You co-developed the Clinical Drug Experience Knowledgebase [CDEK], a comprehensive dataset for drug molecules clinically tested in the US. Could you first describe CDEK and provide an overview of the information it contains?

CDEK is a broad and deep curation of information about clinically tested drugs. That information can be broken down at many levels, from the populations intended for certain treatments down to the molecular and atomic structure of those treatments. For every molecule chronicled in CDEK, there is information about how it works, why it works, who developed it, and whether it was approved for patient use.

The Knowledgebase includes information on mechanisms of action, disease indications, sponsoring organizations, and clinical trial successes, including each publicly reported clinical trial. CDEK’s data can be parsed to assess targeting strategies at the molecular level, how much time it took for drugs to achieve development milestones, the likelihood that a particular drug might be approved, and regulatory approval trends over time.

It seems like CDEK has broad application and could be useful to an industry professional or an academic interested in assessing the likelihood that a drug in development could be clinically or commercially successful. Is it fair to draw that conclusion?

Michael Scott Kinch: Executive Dean of Science and Vice President, Innovation, Long Island University

Absolutely. CDEK could help assess the likelihood of success at each clinical trial phase – and the likelihood of Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approval – of a drug in development. This could inform a range of applications, including competitive intelligence inquiries, business development proposals, and even potential M&A deals.

So, what was the catalyst for creating it? Who might most benefit from using the information in CDEK?

CDEK was developed in the interest of providing transparent and verifiable information and analyses of drug discovery and development. The wealth of information provided by CDEK could help industry practitioners, investors, and other interested parties to inform their understanding of future approval trends and address which stages of development are the riskiest.

You have also coauthored papers using CDEK to explore clinical trial and approval trends for monoclonal antibodies1 and bispecific antibodies and immunoconjugates.2 How could CDEK inform an assessment of the potential success rate of a nascent therapy at each clinical trial phase?

As has been reported elsewhere, the probability that a drug in development could receive the FDA’s approval is less than 12%. That makes the accurate assessment of the likelihood of success of a drug in development extremely important for those who are invested in one. Those concerned stakeholders can perform such an assessment by first accessing information on existing treatments that are similar to their incipient drug.

In short, CDEK offers investors and innovators a lens through which they can take stock of the drug development landscape. CDEK’s information could be one ingredient – albeit a potentially important one – in the context of assessing the likelihood of the success of a new therapy.

How can this information inform business strategy or investment decisions?

Knowing both the likelihood of approval for a treatment and an expected timeline for that approval could help stakeholders assess whether they should continue to pursue the development of one drug over another.

For example, developers of or investors in monoclonal antibodies might find it useful to note that the average monoclonal antibody entering the clinic has somewhere between a one in three and a one in six chance of gaining FDA approval. Also, given the finite nature of patents, those decision makers might also be keen to know that FDA-approved monoclonal antibodies spent a total average of 7.8 years in the clinic.

Industry executives could use CDEK to determine clinical needs that might go unmet, or whether the market for a type of therapy is saturated. That kind of information could be leveraged to provide those executives with insight on whether they should give a green light to continue the development of a new drug. Similarly, investors could use CDEK to assess whether they should fund certain therapies and to better understand and manage the risks associated with their investments.

“CDEK offers investors and innovators a lens through which they can take stock of the drug development landscape. CDEK’s information could be one ingredient – albeit a potentially important one – in the context of assessing the likelihood of the success of a new therapy.”– Michael Scott Kinch

Setting aside investment and business decisions for a moment, might the information contained in CDEK also be useful in the context of a litigation?

It could be, yes. Issues of contention involving drugs in development sometimes require granular analyses over whether a reasonable effort was made to understand the therapies in question. For example, assessing the reasonableness of up-front or milestone payments in a licensing contract or the commercial reasonableness of development efforts or decisions for a given drug in development requires knowledge about the therapy itself and sometimes the likelihood of that therapy’s regulatory and commercial success.

CDEK can provide valuable information about clinically tested drugs in the context of breach of contract, M&A, license agreement, and other disputes. Based on its data about prior experiences with similar drugs and potentially competing products, informed assessment of the likelihood of success of nascent drugs can shed light on whether disputing parties made reasonable decisions about those drugs at issue in a litigation.

Looking ahead, what are some drug development and approval trends on emerging treatments that you have seen in your research?

My research shows an expansion of clinical interest in certain emerging therapies, including bispecific antibodies [bsAbs] and immunoconjugates, which are used to selectively eliminate certain cells, often as part of cancer treatment. In fact, a disproportionate number of these treatments – all 20 immunoconjugates approved to date – are cancer focused.

Although we are seeing that the number of bsAbs and immunoconjugates being introduced to the clinic has been growing annually, it remains to be seen whether this will translate into regulatory approvals. For new fields such as gene therapy and genetically modified cells, prior experiences with other products can be used to identify potential challenges and opportunities. It will be interesting to track the development and approval of emerging technologies such as these that could revolutionize not only cancer care, but also treatments for other diseases and rare conditions. ■

Endnotes

- Kinch, Michael S., Zachary Kraft, and Tyler Schwartz, “Monoclonal antibodies: Trends in therapeutic success and commercial focus,” Drug Discovery Today, vol. 28, issue 1 (2023).

- Kinch, Michael S., Zachary Kraft, and Tyler Schwartz, “Immunoconjugates and bispecific antibodies: Trends in therapeutic success and commercial focus,” Drug Discovery Today, vol. 28, issue 3 (2023).

This feature was published in March 2024.