-

Materialization of Risk in Securities Event-Driven Fraud Class Actions

In this Q&A, Managing Principals Nicholas Crew and Mark Howrey discuss implications for class certification and calculating damages in cases involving events alleged to be the materialization of undisclosed or under-disclosed risks.

Managing Principal Nicholas Crew

In the context of securities class actions, what is the materialization of an undisclosed or under-disclosed risk of an event?

Dr. Crew: Many shareholder class actions are initiated following a “curative disclosure,” in which a company publicly corrects a previous false or misleading statement or omission, which is alleged to have caused a stock price decline. These suits typically allege that the company’s failure to previously disclose this information led shareholders to purchase the company’s stock at a price that did not reflect its true value and then to incur losses when the curative disclosure was made.

What’s different about an “event risk” case, also referred to as a “materialization of risk” case, is that there is not a curative disclosure that directly corrects prior a disclosure of an event that had already occurred. Instead, the plaintiffs allege that an undisclosed or under-disclosed risk of a negative event (in other words, an improperly disclosed risk) materialized when that event occurred and caused a stock price decline. The plaintiffs’ argument is that such an event, while not correcting a prior statement, is an event that would have been foreseeable had the truth been properly disclosed.

How has the materialization of risk been applied and what implications are there for class certification?

Managing Principal Mark Howrey

Mr. Howrey: In a case related to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill [Ludlow v. BP PLC], BP was alleged to have misstated the efficacy of its safety procedures prior to the spill, creating an impression that the risk of a catastrophic failure was lower than it actually was. The plaintiffs argued that, while the spill was properly disclosed when it occurred, the economic effects of the spill, as captured by the fall in BP’s stock price after the spill occurred, were the “foreseeable consequence” of the materially misstated risk of the event occurring. The plaintiffs alleged that, when the major spill occurred, any investor who was defrauded into taking on that heightened risk suffered economic losses and was entitled to damages for the entire stock drop caused by the spill.

When thinking about how investors were harmed, the court made a distinction between investors who would not have purchased the stock had the elevated risks been disclosed and investors who would have purchased the stock given alternative disclosures, albeit at a lower price. The court found that, for investors who would not have purchased the stock, the entire price decline would be an appropriate measure of economic damages. However, for the investors who would have purchased with truthful risk disclosures, the appropriate measure of economic damages would be the difference between the actual stock price and the “true value” of the stock had there been appropriate disclosures at the time of purchase. The court found that, because the plaintiffs’ damages model did not provide a mechanism for separating these two classes of investors, it did not provide a basis to measure class-wide damages. On appeal, the decision was upheld by the Fifth Circuit.

Are there additional implications of the materialization of an improperly disclosed event risk?

Dr. Crew: In a 10b-5 claim, if damages are to be tied to the inflation at purchase caused by the alleged misstatements or omissions, then estimating the inflation as the entire price decline when an improperly disclosed risk materializes in the form of a negative event would, in effect, provide insurance for investors. The stock price decline associated with a bad outcome does not necessarily equal the amount by which the stock was inflated at purchase due to the concealment of risk. That would only be the case if the concealment hid an outcome that would have been completely foreseeable and knowable had the truth been known. In the BP case, the court hypothesized a scenario where the risk of a major oil spill was two percent, but BP’s statements had improperly represented the risk at 0.5 percent. In such a scenario, considering the entire decline as damages when a major spill occurred would overstate the inflation at purchase. While the true probability of an accident was higher than disclosed, the alleged improper disclosures were not hiding the fact that an accident would be happening with certainty or had already happened.

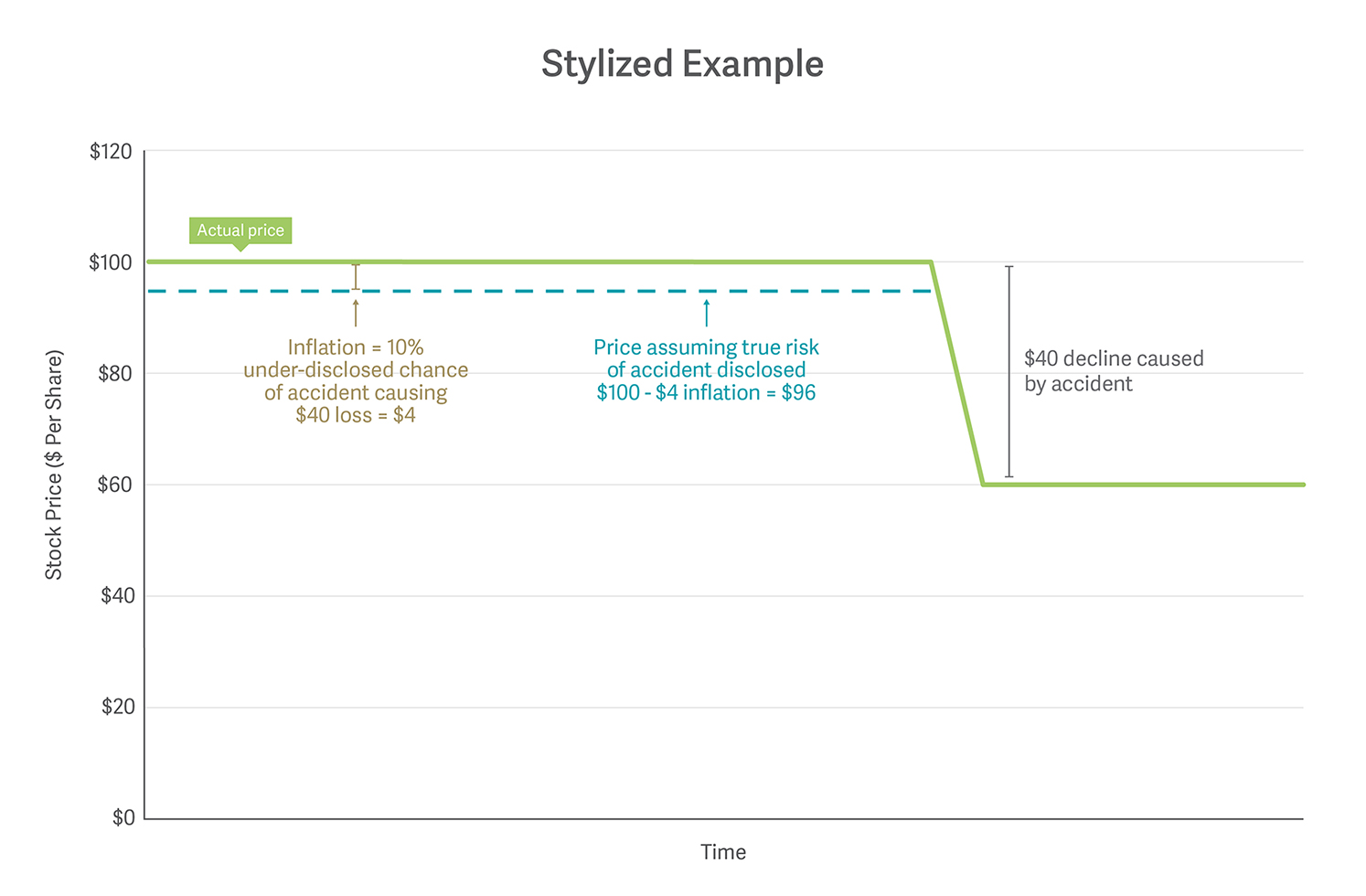

To make this more concrete, consider the stylized example below, where a company’s stock traded at $100 per share during the class period, but experienced a $40 drop per share following an accident. Although the perceived risk of an accident given the actual disclosures at the time of purchase was 5 percent, the true risk of an accident that should have been disclosed was 15 percent – that is, 10 percentage points higher. When the accident occurred and the stock price fell from $100 to $60, in this example it would be incorrect to infer that the alleged misstatements about the risk necessarily led to $40 per share in damages.

Imagine if, instead of an accident occurring, the firm announced that it had improperly disclosed the risk of an accident, and that risk was 15 percent, not 5 percent. Given the $40 loss in the event of an accident (and making some simplifying assumptions), the decline in stock price attributable to such a disclosure would be $4, which is the additional 10 percent increase in the likelihood of the accident times the loss if an accident occurs. This is the amount investors overpaid for the stock (i.e., the inflation) due to the under-disclosure of the risk. The $40 decline when an accident occurs does not represent the inflation in stock price arising from the improper disclosure about the risk.

Mr. Howrey: In the BP case, the court determined that the true probability of an accident was higher than disclosed, but not that an accident would happen with certainty. As a counter example, consider the Massey Energy Co Securities Litigation. In that case, Massey experienced a stock price decline following a tragic mine explosion accident in which 29 miners died. The plaintiffs alleged that Massey made false and misleading statements during the class period about its commitment to safety and safety initiatives. The court denied Massey’s motion to dismiss, ruling that the defendants’ alleged lack of adherence to basic mine safety practices directly caused the explosion. Investors certainly knew that disasters could occur, regardless of the company’s safety precautions, and they could not have known with certainty that such a disaster would occur in the future. Still, from an economic perspective, in ruling that the cause of the explosion was Massey’s safety practices, the court essentially assumed that the market would have anticipated the disaster if the appropriate risk disclosures had been made. In such a case, the price decline upon disclosure of the accident could be used as a basis of the inflation at purchase.

Dr. Crew: These two cases highlight the critical issue in assessing damages in cases involving a allegations of misleading statements regarding the risk of an event occurring. Unless an event was perfectly foreseeable with proper disclosures, using the full price decline when the event occurred would overcompensate an investor for the improperly disclosed risk.

Mr. Howrey: And if the event was not perfectly foreseeable had the heightened risk been known, and an investor tried to claim the full decline as damages, there are issues of individual inquiry. Each investor would have to show that he or she would not have bought the stock at any price to show that he or she was harmed by the entire price decline. ■

This feature was published in June 2018.