-

The Use of Reverse Termination Fees in Merger Reviews

Analysis Group affiliate Edward Rock – Martin Lipton Professor of Law at New York University School of Law – is an expert in corporate law and corporate governance. In addition to his teaching and research, he is the director of New York University’s Institute for Corporate Governance & Finance, and he coauthored the book The Anatomy of Corporate Law: A Comparative and Functional Approach.

Professor Rock worked with an Analysis Group team in a Delaware Chancery Court merger matter that raised questions regarding the extent to which the size of the at-issue reverse termination fee (RTF) was appropriate. As Professor Rock explains in this Q&A, RTFs are fees paid by buyers (rather than sellers) upon termination of an agreement under specified circumstances. In conclusion, Professor Rock notes, “There is no ’typical’ RTF. Rather, RTFs are designed to address deal-specific risks, which of course vary from transaction to transaction.”

Q: When contemplating a merger, what are some of the key risks that the negotiating parties try to manage? What are the components of a merger agreement that address those risks?

Edward Rock: Martin Lipton Professor of Law, NYU School of Law

Professor Rock: The decision to enter into a merger agreement carries with it a variety of legal and financial risks. One key area of risk relates to non-consummation, which can result from a range of issues, including failure to obtain financing, failure to obtain regulatory approval, or simply one party deciding to walk away from the deal. The costs of a failed merger include out-of-pocket costs, time, and potential lost opportunities due to a process that ultimately did not generate value. For selling companies, these risks can be particularly acute because potential buyers may view a failed deal as evidence that there is something wrong with the selling company.

The risk of non-consummation is elevated when merging parties face scrutiny from antitrust authorities. When competing companies attempt to merge, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or Department of Justice (DOJ) may condition approval on the parties agreeing to certain actions, such as divestiture of assets, to ensure that a deal does not pose risks to competition. These requirements can lead to a protracted merger process. And, in the event that an agreement with the regulatory authorities is not reached, the FTC or DOJ may seek to block the deal. Both potential outcomes translate into increased costs and lost opportunities.

There are a variety of terms that can be included in a merger agreement to address these risks, including provisions that define circumstances under which a target or an acquirer may terminate the transaction. The merger agreement may also include a “hell or high water” provision (requiring that the merging parties take any and all efforts to obtain antitrust approvals, including that the buyer divest assets in order to close the transaction) and/or “reverse termination fees” (RTFs).

Q: What is a reverse termination fee?

Professor Rock: An RTF is a fee payable by the buyer to the seller in the event of non-consummation, often due to failure to receive antitrust clearance within a certain time frame or failure to secure financing for the transaction. It is called a “reverse” termination fee to distinguish it from the target termination fees (TTFs) paid by the seller to the buyer in the event that the seller terminates the transaction, often to accept a competing offer. The RTF is often triggered by an “end date” provision, which establishes the date after which one or both parties is permitted to abandon the transaction; if either party does so, the RTF is paid by the buyer.

Q: Are RTFs prevalent in today’s market?

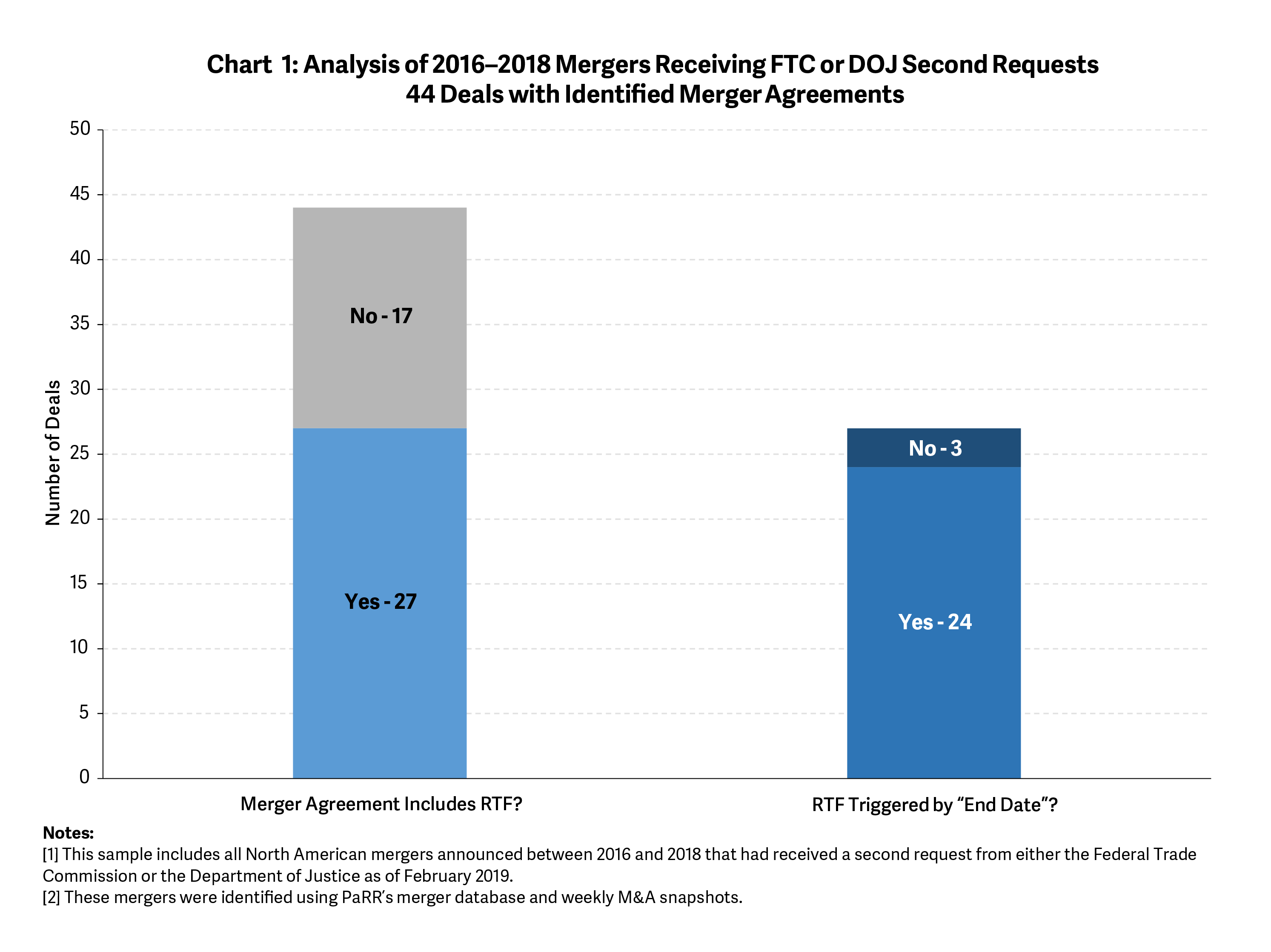

Professor Rock: Depending on the type of transaction, yes. Among transactions that are subject to antitrust risk, RTFs are particularly prevalent. For example, when we look at transactions that were subject to second requests for additional information from the DOJ or FTC – a proxy for antitrust risk – we find that roughly two-thirds of those deals had RTFs. Furthermore, nearly all of these RTFs were triggered by the passing of an end date, which may be established to incentivize the parties to comply with measures required to meet antitrust approvals in a timely manner. In most instances, in fact, the RTFs were to be paid only if antitrust approval had not yet been received by the end date. (See Chart 1 below.)

Q: Why would a company agree to an RTF?

Professor Rock: Selling companies, of course, benefit from the risk mitigation and shifting of some of the costs to the buyer, but buyers often benefit as well from agreeing to an RTF, even a relatively large one. For example, in the event that financing is unavailable in a private equity deal, the RTF protects the buyer by limiting the amount it must pay to terminate the transaction. Additionally, the protection afforded by an RTF provision may result in the seller agreeing to a lower price in exchange for stronger deal risk mitigation provisions. Moreover, given the risks of non-consummation, a target company may require a merger agreement to include an RTF provision in order to enter into a deal at all. Finally, an RTF may increase the credibility of a bid from a buyer with a limited track record.

Q: What is the magnitude of a typical RTF?

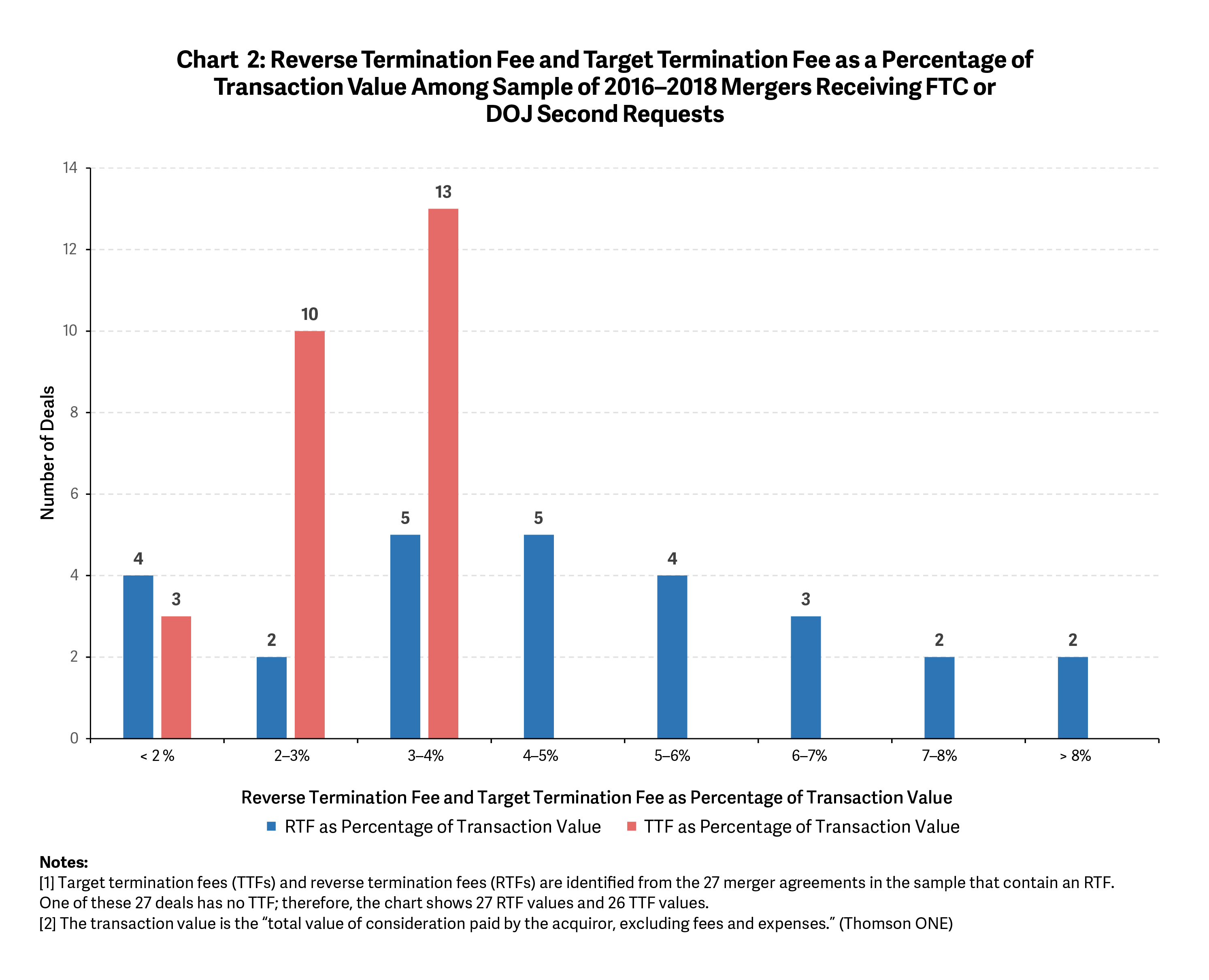

Professor Rock: There is no “typical” RTF. Rather, RTFs are designed to address deal-specific risks, which of course vary from transaction to transaction. Because these risks – including antitrust risk and financing risk – may be quite high, RTFs can also be very large relative to the deal value. This distinguishes them from TTFs (in which the seller pays the buyer), which protect buyers from a different set of risks and which typically represent only a few percentage points of deal value. (See Chart 2 below.) ■

This feature was published in September 2019.